I.

A common lament from people like Wauwatosa’s Finance Director, John Ruggini, or the City Administrator, Jim Archambo, or Mayor Dennis McBride is that it’s difficult to balance the budget because services keep getting more expensive but the State of Wisconsin makes it difficult for local municipalities to raise the additional property tax revenue to cover their costs.

And so each year, every department of the city government comes before members of the Financial Affairs committee, talks about all the great things they’re doing and the extra grants they think they’ll get, and then asks for new office furniture, or an additional employee, or the money to fund this or that new program that totally aligns with the city’s Strategic Plan. And the city has to decide whether they can truly afford all these things.

And usually the department really does need some new furniture and that additional employee really is necessary to accomplish whatever strategic objective the Common Council has decided is very important.

These meetings have been going on over the past several weeks. Unfortunately, the city’s meeting portal still doesn’t have all the recordings available (some are only 10 minutes long, some cut off halfway through), so instead of some broad overview of everything, I’ll just talk about the Wauwatosa Fire Department since that was one that was available.

For the most part, the Fire Department’s presentation requesting slightly more money than last year was pretty straightforward. They spent $14.8 million 2022 and would like to spend $15.8 million in 2023 to pay for new equipment, more overtime, and an additional firefighter so Engine 53 has 4 personnel on it instead of 3. They’re also expecting almost $400,000 in additional revenue from the county and the state through various programs to partially offset these costs.

Overall, of the City’s total proposed expenditures of $73.2 million, the Fire Department spends 21 percent1 of that—exceeded only by the police department—to, from what I can tell, provide a number of valuable services in a very professional manner. But what they don’t do a whole lot of is actually fight fires.

II.

A career in the military can be pretty tough which is why I only do it part-time. As a reservist in the Navy, once a month I drive 50 miles to a Navy base north of Chicago and “drill.” I stay there for 2 days, and I get paid some amount of money. When my wife asks what I did over the weekend, it’s usually some variation of, “Oh, I went to this meeting and it was kind of long and boring, and then I spent several hours waiting for my government issued computer to boot up, and load a bunch of patches, and then restart, and then freeze, and then boot up again. And by the time I was finally able to log on it was time to go to lunch. When I got back I filled out some paperwork.”

Despite not making it sound particularly glamorous or exciting, she is usually envious because while I was gone she got stuck taking care of our two young children which is objectively more tiring and aggravating than whatever I’m doing and it must be nice to get paid for doing something so easy and not have to get up with the kids in the morning, etc., etc.

And then I try to explain that really the U.S. Government isn’t paying me to sit around for two days, attend two or three meetings, and read the news while my computer boots up. What they’re paying for is the option to call me up one day and say, “Hey we need you to get on a plane and go somewhere for...a year. It could be dangerous (probably not) or it could be really boring (more likely), but, obviously, it’s going to be far away and you can’t bring your family with you.” And while they’ll pay me for that too, it’s also just still really valuable for the government to have tens of thousands of people they can call for help and who are contractually unable to say, “No, not today, Government. I’m busy.” Especially if there’s a war. And when I explain this to my wife, I try to make it all sound as selfless and noble as possible so she doesn’t grow too resentful that I just spent the last two days spinning in slow circles in an office chair and having leisurely lunches with friends.

Which is why when I look at firefighters and see them drinking coffee and laughing with their firefighting buddies or washing the fire truck or spending a lot of hours on the hack squat machine, I don’t make the mistake of asking, “What are we paying these guys for anyway? If they’ve got so little to do, why do we keep so many of them around?” Because when your house catches on fire, you’ll be thankful that a bunch of them were sitting there waiting for your call.

But still, if the Wauwatosa Fire Department isn’t really fighting many fires, what are they doing?

It turns out that they’re mostly responding to other types of calls. During his presentation to the Financial Affairs committee on October 20, Fire Chief Jim Case said that while calls for service have risen on average 5% annually for the last 13 years, of the 8,219 calls for service in 2021, only 174 (2%) were actually for fires. Exactly 4,849 (59%) of those calls were for medical emergencies. Another 1,880 (23%) were “service calls” which include elderly people who have fallen and need help getting back into bed (examples here) or forgetful people who lock themselves out of their house. I didn’t know these were things you could call the fire department for but, according to Chief Case, it’s only gotten worse since the pandemic ended:

Based on conferences and discussions from Fire Chiefs around the country we think something happened in 2020 with Covid that people became more reliant on other people now. What we’re seeing now are things we wouldn’t have expected to have 911 calls for in the past. Low level medical—a nose bleed, ‘I stubbed my toe’—you know? Once again […] we don’t want to discourage people from that but there are times that we’re seeing things that really kind of make us scratch our head a little bit. More so now than we maybe have in the past.

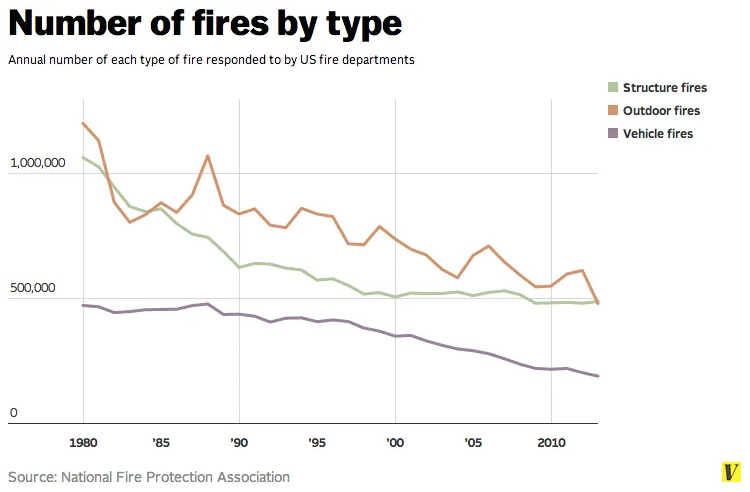

A decline in the actual firefighting that fire departments were created for is actually a nationwide and many-decades long phenomena. As building codes have improved, automatic sprinkler systems have become more common, and materials have become less flammable, there are just fewer fires today than there were 40 years ago. The graph below is a few years old, but shows this secular nationwide decline pretty clearly.

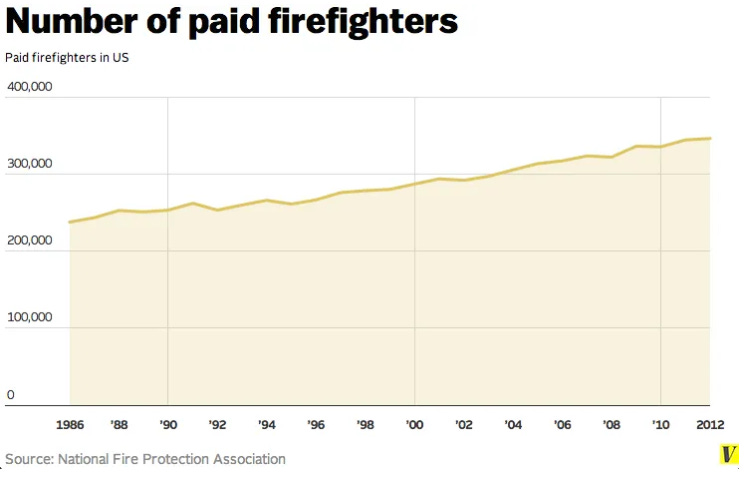

But while the number of fires has declined, the number of paid firefighters in the United States has continued to increase. For instance, about seven years ago it became popular to pair the above graph with something like the one below, and the impression it gives is of some sort of union-generated boondoggle where cities are forced to hire more and more firefighters to do less and less work.

I think there are a couple of counterarguments you could make here:

1.

Perhaps the relevant metric is not number of fires but the dollar value of losses. As homes and property in general have increased in value there is a benefit to more firefighters because individual fires have become much more costly. There’s probably information on this but I haven’t looked into it very deeply.

2.

One might also ask what the optimal level of firefighting is. Perhaps in the past there were actually too few firefighters relative to the number of fires they faced and the increase in the former over the last several decades despite a decrease in the latter better reflects societal expectations. I don’t really have an answer to this, but it is a good question.

3.

Or, maybe just looking at the number of paid firefighters is too simplistic. For instance, paid firefighters are vastly outnumbered by the number of volunteer firefighters in the United States. And paid firefighters tend to be in more populous, urban areas while volunteer firefighters tend to be used in less densely populated rural ones. While the number of fires has declined since 1980, the population of the United States has not only continued to grow but has also shifted away from rural areas and into cities.

As cities grow beyond 25,000 people, their fire departments often move from an all-volunteer to a paid force and so the increasing number of career firefighters might simply reflect this movement of firefighters from one category to another. It’s not that the United States is creating more and more firefighters to fight fewer and fewer fires but that a greater percentage of those fires occur in denser urban areas where people are congregating and which tend to be protected by paid rather than volunteer fire departments.

This graph seems to suggest this might be a partial explanation. While there has been an increase of over 100,000 paid firefighters, it has also been accompanied by a loss of 100,000 volunteer firefighters over the same time period, although it’s kind of noisy and the drop seems relatively recent.

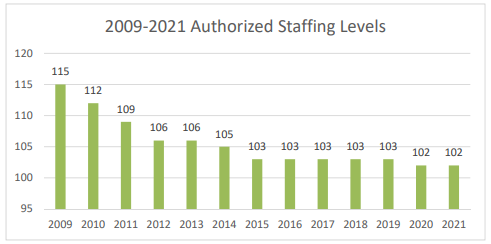

And what you really care about are not the national statistics but what the Wauwatosa Fire Department is actually doing. While I couldn’t find information on how their staffing has changed since the 1980s, at least over the last 13 years they have cut about 13 (11%) of positions:

And they stay pretty busy. Not with fires but with all the ancillary services they’ve come to support over the last several decades. Chief Case, during his presentation on October 20 stressed that some of the firefighters were burnt out and the department was spending more and more money on overtime.

III.

And yet, while I can appreciate that firefighters are actually doing lots of things, I still find the fact that there are fewer and fewer fires and that fighting them consumes less and less of a firefighter’s job to be at least a somewhat compelling reason to ask why we organize emergency services the way we do.

It’s clear that fire departments have adapted over many decades to this changing reality by assuming new duties and responsibilities, training their firefighters to be EMTs and paramedics, doing more community outreach, and that on some level it is easy to justify them doing this because, “the firefighters are there anyway.” We don’t need to send a ladder truck and four firefighters to a car accident just so they can redirect traffic, but we already have the truck. And the firefighters. And the marginal cost is just a few gallons of gas.

At the same time, I wonder if its really the most effective use of resources to spend a lot of money training, equipping, and paying firefighters to help the elderly get back into bed, direct traffic, or attend to people’s stubbed toes.

Imagine you were in charge of some large company or municipal government and someone came to you and said, “I have an idea for a new <object> Department. The organization’s entire culture will be based around dealing with <object>. Little kids will dream of growing up and working for us so they can do important and noble <object>-related work, and the vast majority of our most expensive equipment will be dedicated to handling various <object>-adjacent situations. However, 98% of the time we’re not actually going to be dealing with <object> but instead doing something much different that requires separate training and certification.” I think you’d consider such an idea kind of silly.

But despite many snarky articles about how there are fewer fires and more firefighters, or the well-acknowledged fact that firefighters mostly act as EMTs and paramedics, when I search for things like, “21st century models of firefighting” or “transforming fire departments” or “new policy options for efficient fire departments,” I don’t find many suggestions which makes me feel like I’m missing something obvious about why the current system as it exists is clearly the most effective and efficient way to do this wide range of unrelated tasks.

Nevertheless, I was also struck by what seemed like a relative dearth of research on the basic personnel and resource management problems within fire departments. What’s the optimal number and type of personnel to respond to a call for service? How many of what types of equipment should you have and where to minimize the chances of showing up late with the wrong gear while also not spending exorbitant amounts of money?

Or, how do we evaluate the effectiveness of fire departments? Is it the average response time? The slowest response time?

Is it dollars worth of damage prevented? Number of lives saved?

And are there effective ways to split up or spin-off some of the tasks that fire departments have assumed that might be cheaper but similarly, or even more, effective?

What is the optimal amount of spending on fire protection and what benefits does it produce?

From my—admittedly—cursory digging, the most interesting research on some of these questions actually came from the RAND Corporation's short-lived but productive relationship with the New York City Fire Department in the 1960s. They did a fair amount of work optimizing the allocation of resources and manpower to help control quickly spiraling costs. A lot of their contribution involved mathematical modeling and data analysis that allowed the department to test various manning and response policies and ultimately saved them tens of millions of dollars each year while improving response times and reducing the burden on individual units.2

I don’t know how the Wauwatosa Fire Department currently deploys units, makes decisions on where to stash equipment, or how different shifts are staffed. Perhaps what was novel and cutting edge analysis in 1969 is just the standard way to do things in 2022 but they did acknowledge during their presentation on October 20th that they’re searching for different staffing models and that the experimentation they’ve done so far has been expensive and not particularly productive. And that they would like to hire a data analyst. Maybe if they ever get one he or she can begin by trying to answer some of these questions.

Which seems even more ridiculous if you consider that in the 1970s, fire departments consumed on average about 5% of municipal budgets. See Swersey et al., Fire Protection and Local Government: An Evaluation of Policy-Related Research. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 1975. (pg. 25)

For instance, during union contract negotiations in the late 1960s, the union thought that crews were being overworked and wanted to pair new units with currently overworked units to help divide the workload. This was going to cost tens of millions of 1960 dollars (worth a lot more than 2022 dollars!). After a lot of modeling and testing, the interesting realization was that the benefits would not be nearly as great as union negotiators imagined. This was because as a result of many overworked units in high-incidence areas, those units did not respond to all the calls that came their way. It turned out that if new units were added, they would not be dividing the same workload but actually allowing those overworked units to respond to more calls than they otherwise would be able to. The net effect was that the overworked units would be just as overworked and that most of the benefit would accrue to already lightly taxed peripheral units that now no longer needed to pick up the slack.

Interesting questions.

First, thank you for your service.

Second, nosebleeds and stubbed toe’s?!?! Really people?!?!

Third, as someone who works in product safety engineering, it’s great to see fire numbers going down. Engineering and safety standards are always evolving.

Fourth, we had a crew come to our neighborhood association block party a couple months ago as part of community outreach. They arrived around 4:30 and had been on 18 calls already that day. They left after about 20 minutes...to go to another service call.