I.

You probably know this story by now: About twenty years ago, many municipalities in Wisconsin increased property taxes year after year at a rate that far exceeded inflation. This upset homeowners—since they were paying for it—and the state legislature eventually imposed levy limits that only allowed municipalities to increase revenues by the amount of “net new construction.”

So, for example, if all the property in Wauwatosa was worth $7 billion, a 1% tax would generate $70 million in revenue. If the city wants to generate, say, $71 million in revenue, they can’t do this by simply increasing the tax rate from 1% to 1.014%. Instead, they would need to build $100 million worth of new apartment buildings, hotels, stores, restaurants, &c. and apply the same 1% tax rate $7.1 billion in property value.

Like most policies, levy limits did the thing people wanted it to do plus a lot of things they probably didn’t anticipate. Property tax rates did indeed stop increasing so quickly. But it also expanded the use of Tax Incremental Financing—originally meant to subsidize the revitalization of blighted areas—into the primary tool of municipalities to encourage developers to build new apartment buildings, hotels, stores, restaurants, &c.

And while municipalities can no longer unilaterally raise the property tax rate to generate more revenue than the levy limit allows, they can if voters approve it in a referendum. According to the Wisconsin Policy Forum, the elections in November had “the largest number of referenda to increase local property taxes in our data going back to the implementation of levy limits in 2006.”1

Municipalities do these things because running a city can get more expensive even without any “net new construction.” Medical bills for city employees increase, the police union negotiates better pensions, inflation makes everything 10% more expensive than last year—all add costs but have nothing to do with the addition of apartments, hotels, car washes, whatever.

Infrastructure too. During a meeting of the Financial Affairs committee in February, Finance Director John Ruggini said, “the city has been underfunding it’s infrastructure probably since the 1970s” and “the deferred maintenance is probably on the order of hundreds of millions of dollars.” For instance, the city would ideally repave four miles of road each year, but they’ve actually only been doing about one-and-a-half. Also, between 1998 and 2011 the city spent $8.6 million each year for infrastructure maintenance when it should have been spending $26.6 million per year. If only there was more money to do these things!

Enter the Transportation Utility Fee (TUF). I’ve mentioned this before. One way to get around levy limits is to call things fees instead of taxes. When you turn on the faucet, you’re charged based on the amount of water you use. Those fees defray the cost of maintaining and replacing the pumps and pipes that bring it to you. You could imagine treating roads the same way.

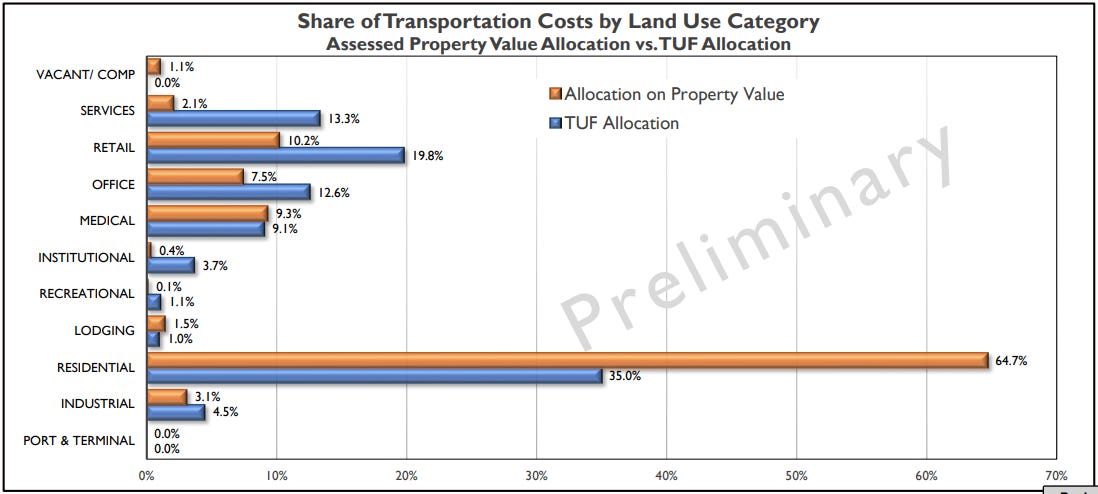

Instead of covering road maintenance and related infrastructure costs with property taxes, each property owner will pay a fee based on an estimate of how much traffic their class of property generates. Gas stations and big box retailers generate a lot of trips and will pay proportionately more while single-family homes generate relatively few and will have lower fees because of it. The estimate right now is $51 per year for homeowners.

But as I wrote earlier:

→ So will this reduce my property taxes? John Ruggini says all else equal, yes, but all else isn’t equal. It is true that we’ll stop raising money through property taxes and instead raise it through a transportation utility fee (TUF) and that if we charged based on what transportation engineers call “traffic generation” rather than property value, homeowners will owe less and other property owners will owe more (the graphic below illustrates this pretty well). But we also want to raise more money in aggregate, so the absolute cost to homeowners may not change much at all.

II.

Of course, big box retailers and other businesses don’t like getting the short end of the stick. Some have already sued.

Wisconsin Property Taxpayers, Inc. sued the Town of Buchanan (pop. 7,200, motto (if you can call it that): “In the Spirit of Town Government”) after it implemented a Transportation Utility Fee in 2019. In June 2022, a judge declared the fee an illegal tax that circumvented the state’s levy limit. My favorite quote from the hearing:

This is going to go up to a higher court. So, somebody, again, smarter than me will be making this decision. And my role right now is to just to give it my best effort and then see where the chips fall.

Can we really ask for much more than the old college try?

The judge found that while the town was authorized to implement the transportation utility fee, such a fee couldn’t be used to circumvent the levy limit. The case was appealed and went to the Wisconsin Supreme Court in March. There’s been no judgment yet.

This would seem to bode ill for Wauwatosa’s transportation utility fee but in a second case, the Wisconsin Manufacturers and Commerce sued the Village of Pewaukee for doing the same thing. This was the case Mr. Ruggini cited during his initial proposal of the utility in September, 2022, when he told the Financial Affairs committee that they would feel more confident going forward with their plan after seeing how the Village of Pewaukee’s lawsuit was decided.

In March, a judge decided in favor of the Village of Pewaukee, finding that they had the authority to impose a transportation utility fee and that it was indeed a fee and not a tax. According to the Waukesha County Freeman, the judge “cited from a precedent opinion that states: ‘The primary purpose of a tax is to obtain revenue for the government, whereas the primary purpose of a fee is to cover the expense of providing a service or of regulation and supervision of certain activities.’” This sounds like two different ways of saying the same thing—what does the government obtain revenue for if not to provide services?—but maybe there’s more to it.

My best guess as a non-lawyer who could find only a few of the actual source documents is that Villages and Cities (but not Towns!) have Home Rule Authority which give them broad powers to do what they want. This is, at least, the authority City Attorney Alan Kesner asserted allowed Wauwatosa to impose such a transportation utility fee. Other differences, based on the Town of Buchanan’s appeal to the Wisconsin Supreme Court, include the transportation charges being explicitly identified as taxes (rather than fees) and showing up on the person’s property tax bill.

With Pewaukee’s favorable judgment, city staff feel more comfortable proceeding with their own plans, and on May 16th, Public Works Director Dan Simpson described how the new transportation utility fee would be implemented.

The hope is that we can make our way through the common council approval process potentially as soon as late-July, early-August so that city staff has time to prepare behind the scenes to actually be able to implement the fees in early-2024. It’ll take quite a bit of staff time and resources to build out the behind-the-scenes billing information and also work with businesses between August and go-live to make sure we’re 100 percent accurate with our data so that everyone’s being billed fairly through that system.

The city plans to mail individualized letters to all affected businesses in June detailing expected costs once the system is implemented in 2024.

Ald. Andrew Meindl said that while he does “think the transportation utility is a great idea especially with everything going on at the state right now,” he worried that communication is lacking.

Not to be a downer, but I can tell you at least in my neighborhood with the transportation utility, the narrative that’s running around—that it’s another tax—is winning. At least in my neck of the woods. On the alder side, while I think it is in our purview to be a spokesperson and raise awareness on this particular issue and at least from my understanding the overall tax burden will be reduced on the taxpayer through this program, I don’t think that that’s necessarily getting across.

Ald. Margaret Arney said she’d received emails from constituents who were suspicious of the new charge:

I’ve had two constituents take issue with the transportation authority and essentially I think their concern is that they’re not sure why they’re getting charged what they’re getting charged. […] I feel like it’s a little bit hard for them to really get why we need this whole separate structure. There’s like a suspicion there.

Mr. Simpson responded that one big advantage of shifting to a transportation utility fee is that they can bill all properties, even those that are not taxable (like hospitals). Another benefit is that it places the cost on the property-owners who generate the most traffic and wear-and-tear on the road. “A single family home has the least amount of impact on our transportation network. It means it has the least amount of cars, the least amount of trips coming and going from that property any given day.” He also promised a website with more information on the new fee and how it would work. “There’s nothing sneaky going on,” Mr. Simpson said.

For instance, following the November 2022 elections, the Wisconsin Policy Forum reported a record year for referenda:

After combining the 18 fall and 11 previous referenda, the $23.8 million in new annual levy authority approved in 2022 is by far the most in a single year and more than triple the amount of the next highest year. Though still a relatively modest part of overall municipal and county levies, which typically grow by $120 million to $150 million per year, these referenda could have much greater effects if taken up by more large communities.

Voters approved fewer than seven measures in each year from the implementation of levy limits in 2006 to 2017. In 2018, 14 municipal, town, and county referenda passed in total. Still, the amount of new levy authority approved in 2022 ($23.8 million) is nearly equal to the total amount approved from 2006 until last year ($25.6 million).