Planning for Schoonmaker Creek Proceeds

The Department of Public Works will focus on two potential solutions for reducing flooding within the watershed

[Note: This will be the only post this week. The Common Council has begun its August recess. I will also be on vacation over the next two weeks, so there will be no updates unless something really spicy happens.]

In 2020, the Southeastern Wisconsin Regional Planning Commission (SEWRPC) proposed 16 potential solutions to eliminate flooding problems experienced within the Schoonmaker Creek watershed during heavy rains. On July 26th at the Community Affairs committee meeting, the Wauwatosa Department of Public Works proposed eliminating 13 of them for reasons that ranged from, “This won’t actually eliminate the flooding,” to “This involves buying people’s homes and knocking them down,” to “The City doesn’t want to operate a dam,”—leaving three that they wanted to study in more depth and develop cost estimates for over the next 1-2 years. After the presentation, Ald. Lowe said:

I'm just really disappointed that this is even coming to us now. It seems like this really should have been addressed 5 years ago, 10 years ago;—that's it's taken this long to even get to this step…I'm equally disappointed hearing that it’s going to take another 2 years in the process to get to another step. If it was up to me, I would like to see a shovel in the ground tomorrow, to get this going.

[It’s] neither here nor there. I just think that we really have to as a council and a city really get a hold of this thing and come up with a solution as quickly as possible.

Before proceeding, I do want to point out that I think this is not an ideal way to handle complex problems that will cost taxpayers tens of millions of dollars. It reminds me of the politician’s syllogism:

Something must be done.

This is something.

Therefore, we must do it.

Anyway, he put forward a motion to eliminate one of the three remaining options from consideration because it involved expanding the size of an open channel that ran through the Washington Highlands neighborhood. Residents of the Washington Highlands thought this would be dangerous, ugly, and annoying and expressed these concerns during the meeting.

In the end, the committee unanimously approved a motion to investigate and develop better cost estimates for only two of the original 16 potential alternatives presented in the original SEWRPC report. On Tuesday, August 2, after a brief discussion, the Common Council approved this course of action.

The two options the Department of Public Works will study are:

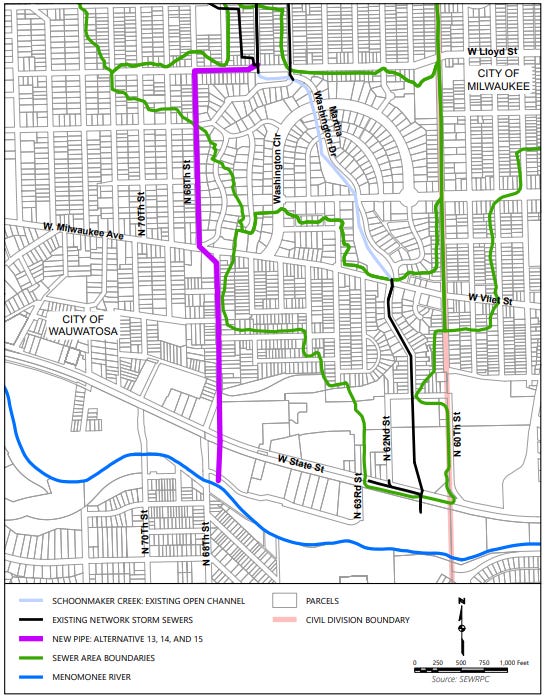

Alternative 15—the Tunnel—which involves enlarging 14,700 feet of local storm sewers north of Lloyd Street and up to Center Street. It also includes an approximately mile-long, large diameter tunnel to take that water to the Menomonee River.

Alternative 16—the Bypass—which involves 12,900 feet of enlarged local sewers and, instead of a tunnel, a large bypass storm sewer underneath Martha Washington Drive from W. Lloyd Street to Milwaukee Avenue to convey water that would otherwise go into the open channel.

I have two main concerns.

It's tough to make predictions, especially about the future

First, a short digression.

The Department of Defense has a tough job. You might not believe it, but it’s actually pretty difficult to spend $715 billion dollars efficiently. Some of it goes to soldiers, sailors, and Marines which is pretty straightforward (or should be), but a lot also goes to things like designing new weapons, planes, satellites, and ships which can take a long time to design and have to be useful for decades even as technology improves, or threats you thought were really important become less threatening while things you never thought were threatening before suddenly take on dire and immediate importance.

For instance, Lockheed Martin started developing the F-35 in 1995 and it only went into full-production last year. Whatever was state-of-the-art in the mid-90s is most certainly in landfill today. But at least people still want the F-35. You can amortize those development costs over the thousands of planes you’ll build for your own military as well as the thousands you’ll sell to foreign countries.

But no one really wants the Seawolf-class submarine. It was designed in the 1980s to counter the Soviet nuclear threat posed by their sophisticated Typhoon-class ballistic missile submarines just like the one Sean Connery stole in The Hunt for Red October (minus that weird caterpillar drive). The Seawolf could go deeper and faster than anything the United States had built before. And they had 8 torpedo tubes! Twice as many as the USS Dallas. They were so cool, we wanted 29 of them.

But then the Soviet Union collapsed and no one needed a submarine that could go deeper and faster than anything that had ever been built before. Their fancy Sean Connery-conveyance machines mostly sat through the 90s rusting along the pier. So we stopped building the Seawolf after the third one was finished for an all-in cost of $3.5B each.

Infrastructure has the same problem. You build something that takes a long time and costs a lot and hope it will be useful for decades to come. But sometimes you build a city and no one omes to live there. Or you build a sewer wide enough to handle the most severe rainstorms of the last 100 years, but the rainstorms over the next 100 years are even bigger and you end up with just as many flooded streets as you had before.

I don’t know if this will happen, but it seems like something we should be concerned about.

Previously, in Schoonmaker Creek: A Guide for the Perplexed, I mentioned that the SEWRPC report used historic rainfall data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to model surface flooding in the watershed. This appears to be the basis for the pipe width they think will be required to minimize flooding during a 100-year rain1.

But in a RAND study of flooding in a Pittsburgh watershed, they compared this same historic NOAA dataset to 16 years of more recent locally-generated data. Based on the NOAA data, they:

Expected approximately 8 24-hour events where at least 2.3 inches of rain fell, but over this period we observe 18 events meeting or exceeding this threshold. For the 5-year event, we would expect just over three 24-hour storms of at least 2.9 inches but observed 10 events of this size or greater.

This comparison shows that the count of extreme 24-hour rainfall events observed in Negley Run during this period is consistently greater than the median Atlas 14 projections would suggest at all frequencies.

Severe rainstorms occurred 2-3 times as often as would be predicted by historical data. You may have previously seen a graphic like this:

The point is that a small increase in average temperatures (or in our case, average rainfall) corresponds to a much larger shift in the frequency of extreme temperature (or rainfall) events. Climate change will likely make severe rainfall more frequent and more severe. And it would be bad to design a sewer system based on the amount of rainfall we’ve gotten in the past only to get more frequent and intense rainfall tomorrow that the system is not designed to handle. Unfortunately, there’s no mention of climate change in either of the two reports I looked at.

And there are other sources of uncertainty: Population and land-use trends are uncertain2, the fiscal environment is uncertain, advances in technology are uncertain, and the political environment is uncertain. But none of these are being explicitly considered as the Department of Public Works narrows down the range of options it considers.

For instance, how will it be paid for? Both of the alternatives being considered will be pretty expensive. The SEWRPC report provides estimates of $30-40M dollars but this doesn’t include all relevant costs, and some members of the City Staff have mentioned total costs closer to $100M dollars. But there are also cost overruns and inflation to consider.

Cost overruns. I would expect there are better articles out there than this one that uses data from the 1970s, but my intuition is that the problem has gotten worse not better since then, so let’s use it anyway. It says that on average, public infrastructure projects cost 50% more than planned. That means a $100M project could cost closer to $150M.

Interest. My perception based on relatively little is that the City is managed in a prudent and financially conservative manner. But even a prudent and financially conservative Wauwatosa seems unlikely to be able to pay cash for a $150M capital improvement project. I’m not super confident that I’m thinking about this the right way, but Wauwatosa seems like it tends to issue debt at rates of 2-5%. Assuming 4% interest on $150M in debt gives a total cost over 25 years of about $237M, or an additional $9.5M expense each year in principal and interest payments.

I have no idea how they plan to raise this extra money, but as a point of comparison, the 30% increase to our water rates that was recently approved will raise an additional $2.8M per year in revenue. That’s an increase to an average user’s water bill of about $27 per quarter. Raising an additional $9.5M per year in revenue would add another $92 per quarter to your water bill.

But interest rates are uncertain. And if we were certain how large cost overruns would be, we would presumably incorporate them into the original estimate.

Public infrastructure investments used to be more straightforward because there were fewer stakeholders that needed to be listened to, systems were more independent, and change was relatively slower and more predictable.

But things change more quickly and unpredictably today, there are many interlocking pieces, and making a decision that will need to be useful for many decades based on conditions at a moment in time is risky.

Really? Only two?

What if you get halfway through a project and realize it’s going to cost 50% more than you expected and won’t reduce flooding to the extent you thought it would due to increases in rainfall?

Across many decades of experience trying to grapple with uncertainty and figure out effective ways for the Department of Defense to make big investments in new weapons or help cities like Pittsburgh and states like Louisiana build infrastructure that will operate well across a range of possible futures, researchers who care about these things find that the best solutions tend to be those that are flexible, that can be re-evaluated as more information becomes available, and that allow for various mitigations or hedges to minimize the impact of the unexpected.

But it doesn’t really seem as if the City is thinking in those terms.

One of the alternatives—the Tunnel—was described by City Engineer Bill Wehrley as akin to “ripping off a band-aid.” Once you start, you really have no option but to finish it. This seems like the opposite of flexible.

The other alternative—the Bypass—seems even worse in some ways. You could conceivably put in the larger sewer pipes north of Lloyd St. and then stop if something changes (like maybe you run out of money). But without the channel bypass, that just means you’ll have a greater volume of water flowing through the open channel in the Washington Highlands. It will be even more dangerous and dirty than it was before.

And the third option, of course, was eliminated because the residents of Washington Highlands said it would be ugly and dangerous. I don't necessarily disagree. But rather than dealing with it in an ad-hoc way by listening to some complaints and then immediately eliminating it from future consideration, it would be useful to evaluate these concerns against other things we care about—like cost, or the ugliness and danger of the alternatives.

We can bore a tunnel for $40M dollars. Or we could widen a culvert through the Washington Highlands for $30M dollars. How much do people value aesthetics and safety? And what if we could spend a little more money to mitigate these safety concerns or make it less of an eyesore? Could we build a not-ugly fence and plant a bunch of trees along the newly widened culvert for less than $10M dollars?

No idea. It would be nice if somebody could put in a big table or a presentation somewhere a statement that said, “we considered the not-ugly fence and found it to be very expensive and still-ugly,” but by eliminating it from consideration entirely, we’re at least implicitly saying that safety and aesthetics are worth somewhere between $10M and infinity dollars and that there is no possible way to achieve these things for less than that.3

Instead of singular solutions, you want strategies, combinations of options that allow you to reasonably accomplish multiple objectives and provide flexibility in case the future turns out in a way the original design doesn't anticipate. It's not about optimal solutions. It's about tradeoffs among competing values and minimizing regret.

As an alternative, consider RAND’s study of stormwater management strategies for a watershed in Pittsburgh, in which they:

[E]valuated 17 possible stormwater management strategies for Negley Run based on the core concept of a new centralized and daylighted GSI [Green stormwater infrastructure] system. These strategies would utilize both green (e.g., wetlands, streams, ponds) and gray (piped) infrastructure, store a large volume of rainfall during and after storms, and provide a new pathway for stormwater to flow directly to the Allegheny River along the Washington Boulevard corridor instead of flowing through the combined sewer system. They also include other amenities, such as a multipurpose recreational trail for walking and biking.

We identified these strategies using a plan and literature review, design-focused participatory workshops and stakeholder engagement, and formulation and iteration with technical experts. Each strategy is defined by the geographic area it covers and the level of investment to be applied within that area. We identified nine cumulative strategy increments (1 to 9) based on geographic area, where each additional increment also includes the previously numbered increments so that the strategy builds “upward” from the bottom of the watershed into the surrounding neighborhoods. We also identified three options (A, B, and C) for different levels of investment to be applied within selected increments.

They also considered multiple scenarios based on various changes in climate, development and land use, and the number of wastewater customer connections. They then evaluated the performance of these different strategies across each of these scenarios.

I do think the City has done some of these things—there have been community engagement meetings and they’ve considered a few green infrastructure options. And Schoonmaker Creek, despite its unprecedented costs for the City of Wauwatosa, is probably a less complex undertaking than the situation Pittsburgh is facing. But I still think something like the above is a useful model that could have a better chance of finding good solutions than the process that’s being used now.

Or the amount of rainfall that has a 1% probability of occurring in a given year.

More intense development leads to less grass and more impervious surfaces that don’t absorb water.

And this is of course ignoring the fact that many who spoke out against the wider channel (Alternative 6) did so because they feared that widening it would increase the speed of water flowing through it and make it more dangerous. But the SEWRPC report explicitly said this would reduce the velocity of water going through the Highlands. On page 61:

It is worth noting that Alternatives 4, 5, 6, and 9 include armoring a portion of the existing Schoonmaker Creek open channel that would mitigate the effects of higher flows. The open channel improvement included in these alternatives would protect the channel by decreasing flow velocities, increasing the channel capacity, and armoring the open channel for flows up to the 10-percent-annual-probability event.