Mayor says solution to lack of affordable housing is more housing

Not as obvious as you might think.

I.

People get worked up about housing. Nationally. Locally. Especially some members of the Common Council. I've written a little about it before (see here).

The term NIMBY (Not In My Back Yard) is more bestowed than assumed—I don’t think a NIMBY would call himself a NIMBY. The same goes for variations that I’ve never heard before but that Wikipedia assures me exist, like BANANAs (Build Absolutely Nothing Anywhere Near Anyone) and CAVE dwellers (Citizens Against Virtually Everything).

The economist Noah Smith, helpfully distinguishes between several -IMBY species.

→ The right-NIMBY is easy to despise. According to their detractors, they oppose more housing because they are racist and don’t want “the poors” or “brown people” living near them. They’ve already “got theirs” and don’t mind pulling up the ladder of homeownership and prosperity behind them. They are generally perceived as selfish, bigoted, and excessively worried about their own property values.

I’ve never actually heard anyone explicitly express all of these views (I have heard the property values one) maybe because it’s a caricature, maybe because I live in a bubble, or maybe because people, if they have these opinions, tend not to express them publicly.

→ The left-NIMBY, despite his opposing political orientation, comes to the same conclusion by different means. He doesn’t oppose the new apartment building near his home because it’s not nice enough, but because it’s too nice. Rather than more “affordable,” below-market rate units for low-income households, he proclaims, the city only demonstrates its malign neglect of the marginalized and working poor by allowing greedy, profit-hungry developers to build ever increasing numbers of “luxury” apartments that are not only unaffordable for the non-wealthy, but that make the apartments around them unaffordable too through gentrification and induced demand.

→ The YIMBY, by contrast, says loudly and emphatically, “Yes In My Backyard” to all of the above. Bred in the harsh and unforgiving NIMBY-stronghold of San Francisco where young Millennials pay rent to sleep on someone’s porch or share a bedroom with three roommates, they despise the parochialism of the right-NIMBYs. But they hold even greater contempt for the left-NIMBYs whose economic ignorance makes them impervious to the fundamental realities of supply-and-demand.

The YIMBY will tell you that the way to make housing more affordable is just to build more of it and that whatever local concerns you might have about parking or maintaining “neighborhood character” are more than outweighed by the damage done to young families by preventing them from living and working in more productive cities or to the country by preventing landowners from using their property in more economically efficient ways.

II.

While these caricatures partly reflect the peculiar failures of some large, coastal cities and don't map perfectly onto smaller midwestern ones I do think it's a useful frame for understanding the Common Council’s discussion on January 17th concerning the final approval of The Foundry, a proposed 289-unit residential development at 11220 West Burleigh Street.

The most articulate opposition came from Ald. Meindl who said he’d vote ‘yes’ this time, but that he might not be such a Mr. Nice-Guy in the future.

Here we are again. More luxury apartments. […] [M]ore luxury apartments puts more strain on what very little we've got going on to try to get people going into homes. The Community Land Trust formation committee is going to start meeting soon which is exciting. But the resources are simply not there to combat us jamming in all these luxury apartments. I did appreciate that those apartments were going to be ADA compliant.

[…]

[W]e have to start taking a stand at some point and saying, “Look, I understand, the state levy limit.”—and it's getting to the point with my constituents that they're like, “Yeah, yeah, Andrew, we know. But more luxury apartments? Come on man. Where are the townhouses, the condos?”

And I understand: not profitable. But then it's just extremely frustrating because the way that the business and the market has functioned is that then the developers come back and say, “Give me my TIF money if you want anything good for the community.”

[...]

I think we need to start looking at our strategic plan and make sure that the developments coming in to Wauwatosa align with the strategic plan and we are making it […] a welcoming community to live, and try to get away from luxury apartments. It's just getting overwhelming at this point. I will be voting in favor of this tonight, but I'm starting to reach my limit of how many times I'm going to vote ‘yes’ for developments like this.

Alders Meindl, Joseph Makhlouf and Megan O’Reilly also mentioned the strain that dense development puts on local infrastructure, especially the additional traffic on nearby roads. Ald. Makhlouf added that all these potential phases of future construction are beginning to feel like “development for development’s sake” and that “the developers—clearly they haven’t asked for it yet—but they’re going to be asking for TIF funding.”

Mayor McBride finally says:

I'm going to disagree with some of the statements here. There was a long article in The Atlantic magazine about a month ago about the extreme housing deficit in our country. Ever since the Great Recession our entire country has been underdeveloped in terms of housing. We have young people, my children, in that generation. People in their 20s and 30s can't find housing at an affordable cost. Why? There's not enough housing.

The point that this woman made—and she was an affordable housing advocate—was that any housing that gets built increases the supply of housing. And if we remember our basic economics course, and I'm no expert economist, but when supply goes up, cost goes down. When demand goes up and supply doesn't go up, cost goes up. That's why we have an affordable housing crisis. Because we don't have enough supply. [...] All housing, whether it's luxury or affordable increases the supply and makes all housing more affordable.

At the same time we have a companion development that we've been pushing through that is an affordable housing project. Right next to this. So it is not as if we are focused solely on luxury housing. That is completely incorrect. [...] We have a severe housing shortage, not only in the Milwaukee area, not just in Wauwatosa, but across the country.

[...]

I'm not telling you how to vote tonight, but I'm telling you please don't have misconceptions about the market, the plan, and anything else. Be concerned about traffic, be concerned about an overload, be concerned about whether we need a roundabout or a signal and that sort of thing. But please don't misstate the market, because it's just not accurate.

I mostly think this is correct, and a lot of the effort to understand the effects of new housing on surrounding rental prices or the effects on economic growth from constricting supply support this (I don’t know what article from The Atlantic he’s referring to—maybe this one or this one—but they mention some of this research). But I will briefly mention two things that sometimes get glossed over—long-run versus short-run effects and winners versus losers.

If you could set down 2,000 new apartments instantaneously, the market price for an apartment would immediately drop and everyone would notice it. It’d be easy to say, “More housing reduces rents,” and people would believe you because they could see it themselves. But in reality, housing doesn’t appear instantly. It can take years to finance, design, approve and build. In that period even more people may have moved to the area, pushing up prices even further. And telling someone that, yes, prices continue to go up year-over-year but less than they would have if no new apartments had been built at all—even though it’s usually true—is just less persuasive.

So there’s a lag. And not only does that mask the price-reducing effect of new housing, but some people can’t afford to wait. The demand for cheaper apartments, condos, and townhomes partly comes from the retired and elderly who want to downsize from their single-family detached homes. I don’t want to be too glib about it, but they don’t have an unlimited amount of time to watch this all play out.

So when people complain that rents are too high, an answer like, “build more houses” is correct but slow, the impacts are hard to see, and it’s not particularly gratifying for elected officials or for constituents who want to see cheaper places right now.

Also, while building more housing might be beneficial on average or in aggregate, there are always winners and losers. Unfortunately when it comes to housing, the losers already live here. They see their view obstructed or the traffic get worse or their way of life disrupted, and they also vote in elections and attend common council meetings. Conversely, the winners (future renters or homeowners) usually haven’t even shown up yet.

These problems are exacerbated by the fact that as home prices increase and become a larger portion of someone’s total wealth, it tends to make them more risk averse and likely to oppose anything that might upset the status quo. The same holds true not just for a house but for a community. There are lots of benefits to having a strong sense of community and close neighborhood ties but one downside might be that such ties are usually predicated on some existing state of affairs that is highly valued and that people are hesitant to tinker with.

III.

Solving this problem probably means doing lots of things at the same time. Some of these the city is already doing. Some of them they could do.

While I was somewhat critical of the Community Land Trust proposed by Ald. Meindl last July, one upside is that it provides some positive benefit in the short-term—a cheaper house or three—while allowing larger but slower-moving reforms and changes—like building hundreds or thousands of apartments—to have their impact.

Using TIFs to subsidize the creation of affordable housing units within larger mostly market-rate development projects also has this benefit of attacking the problem at different time scales. The affordable units have a large and immediate impact for the people who get them while the addition of many more profitable market-rate units slowly reduces the city’s undersupply of housing (and encourages other developers to build as well).

Alders might get upset about greedy developers asking for TIF money to “do anything good for the community” but you could imagine offering other incentives—like zoning abatements that remove density or height limits or streamline the approval process—if developers offer some minimum number of units at below-market rates. This would have a monetary value to the developer while being costless (or maybe cost-saving) to the city.

Finally, some of the Zone Tosa For All proposals also bridge this gap between winners and losers and between short- and long-term benefits. One of the more significant proposals included shifting the zoning code from regulating density to regulating building size. For example, instead of limiting a property to no more than four residential units, they would allow a building to have as many units as desired subject to height or setback restrictions. Like this one:

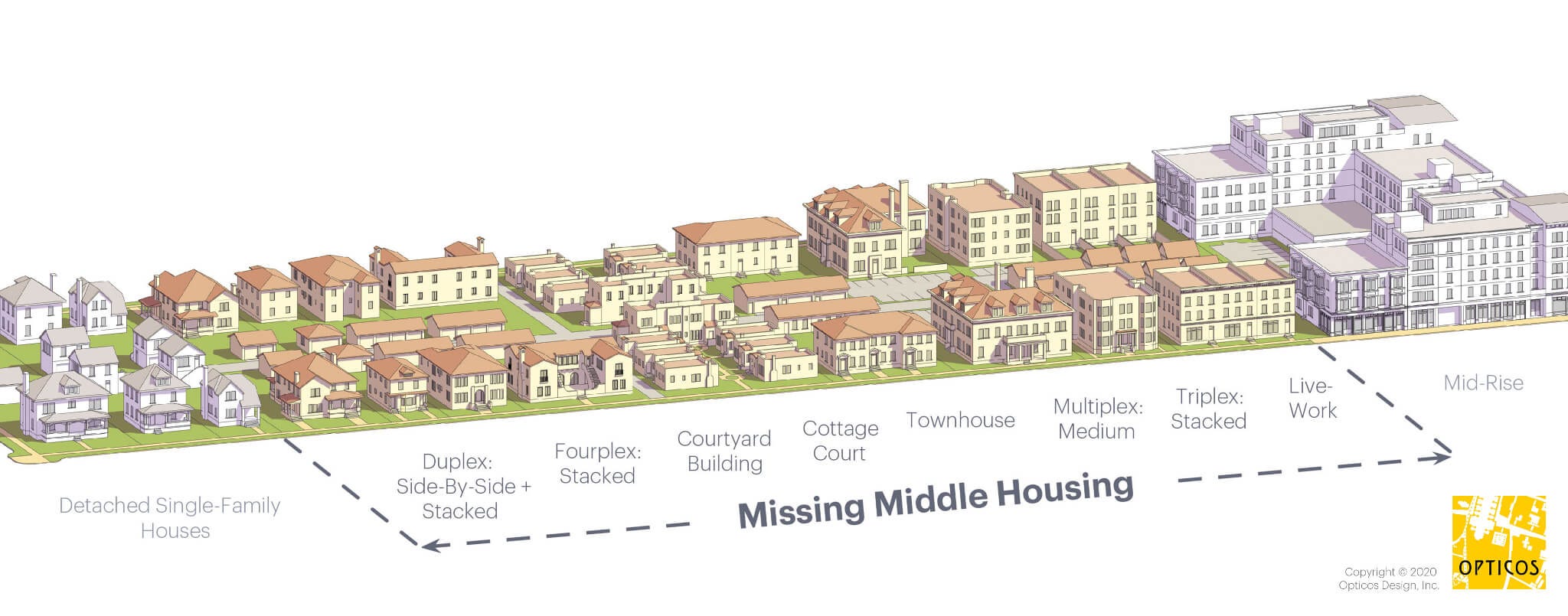

The hope is that this would encourage more of what some proponents call “Missing Middle” housing—multi-family residences that lie between single-family homes and large mid-rise apartment buildings. For instance, the picture below identifies duplexes, fourplexes, courtyard buildings and cottage courts, townhouses, stacked triplexes, and live-work buildings that would allow more gradual, long-term densification while also being more aesthetically pleasing and less obnoxious to nearby homeowners than a big 5-over-1.1

These aren’t easy problems to solve, but I think the City is generally taking the right approach. The Common Council approved plans for The Foundry by a vote of 15-1. Ald. Makhlouf was the lone dissenter.

I think this is a good idea; however, it assumes that the primary reason these aren’t being built is because of restrictive zoning regulations and not, for instance, lack of demand, low construction efficiency, or lack of financing. For example, this recent Journal Sentinel article suggests that a lack of financing is the primary reason so few condos are built in Milwaukee County. In the early-2000s developers and banks lowered lending standards and built lots of condos but have since realized in the aftermath of the Great Recession that they are less profitable and more of a headache than they expected.