Excel-erating the school board into the future

Failures of strategic planning and how to be explicit about tradeoffs

I. Three Quick Scenes

An Inservice meeting on January 5th:

During a special school board meeting several weeks ago, board president Eric Jessup-Anger presented a short statement for discussion that I think was variously referred to as the board’s vision, ethos, or “North Star.” The idea was that by making such a “North Star” explicit, it would provide a common reference point for board members and make decisions easier.

The meeting wasn’t recorded, but from my notes the “North Star” he proposed was something very close to:

The board will have a relentless commitment to academic excellence for all students. No exceptions. We will hold ourselves accountable by developing the resources, structures, and systems for our district to thrive.

Board member Sharon Muehlfeld had some suggestions to tighten up the wording and wanted to emphasize measuring accountability.

Board member Jessica Willis thought it aligned well with the district’s Strategic Plan.

Board member Leigh Anne Fraley thought it managed to convey a lot in relatively few words.

Board member Mike Phillips didn’t have much to add.

Board member Jenny Hoag said that while she didn’t disagree with anything in said, she wasn’t sure how it would actually guide the work the board plans to do or help the board make decisions.

Board member Mike Meier described it as a truism, a redundancy, and a “fluffy thing” that obfuscates very serious problems that the school district and board face.

They discussed some revisions for a few minutes and then moved on to other things.

A school board meeting on November 28, 2022.

I quoted this previously, but in accordance with the district’s strategic plan, CFO Kevin Brightman proposed hiring a consultant to project future demographic trends in Wauwatosa and provide an estimate of future enrollment. Board member Sharon Muehlfeld wasn’t enthusiastic:

We have a lot of work to do on student achievement, and I feel the risk to having this data and working on it is to […] focus on a path that we may not be ready for. And that means restructuring.

Right now our footprint is two high schools, it’s neighborhood elementary schools, and that's what Wauwatosa values […] Any changes to that structure which likely would be the result of decisions based on data out of this report—to me—it [gets] the community focusing on something negative when it it could be very positive […] I personally believe our city deserves two high schools, and if we change our structure that might not be the case, so I want to see us focusing on innovation [and] improving student achievement.

[…]

I just have for 18 years heard people being very upset about the boundary changes.

A budget presentation in May, 2022:

Also mentioned previously, in May of 2022, both the outgoing and incoming CFOs presented the proposed budget and 5-year financial projections with revenue, enrollment, and spending estimates to the school board. Mr. Meier said afterward:

There are six to seven fundamental assumptions here which run contrary to everything I have come to understand while serving on the board […] A lot of things have to go perfectly for this whole thing to work, and some of these things have never happened before—realistically. We would have non-resident enrollment at the highest level ever. We would have resident enrollment at the highest level in over 20 years. We would have an increase in pupil aid which we've been praying for for many many years. It has cuts in health care benefits, decrease in base wages. I don’t know how.

II. One way to grapple with messy, uncertain problems

Most important decisions involve uncertainty and risk. You don’t know everything you’d like to know. Some of the things you don’t know are perhaps knowable but will cost time or money that you may not have. Some things, like predictions about the future or individual behavior, are mostly impossible to do with any certainty. In either case, you must choose one option among many because resources are limited and you can’t do it all.

One broad lesson from the literature on making hard decisions1 is that it’s better to acknowledge this uncertainty and figure out ways to deal with it as you design and consider different choices. Another lesson is that in the presence of uncertainty, you should leave yourself some ability to adapt to a changing situation. Instead of the “optimal” solution that achieves everything but only if all your assumptions are correct, you want the solution that minimizes regret and performs decently under a wide range of circumstances.

This is not really intuitive. People don’t like uncertainty—either considering it or presenting it. Partly, because it can be difficult or impossible to quantify and people have a real fetish for numbers, and partly because it’s uncomfortable to tell your boss you don’t know things. One alternative is to ignore it entirely. Another option is to bury it in a footnote or at the bottom of a PowerPoint slide in small text which provides for some plausible deniability if things go south but perhaps avoids uncomfortable questions.

Over the last nine months I’ve had the chance to talk to parents, former administrators, some current and former board members, and district staff members, as well as hear people complain, suggest, yell, demand, and discuss a wide range of things at board meetings.

Here is a long list of some of those things:

People are worried a new enrollment projection might not be accurate.

People are worried that the state won't increase education spending.

People are worried that household sizes will shrink and resident enrollment will decline.

People are worried that it takes too much time to close an old school or to build a new one in response to changing resident enrollment.

People are worried that increasing open enrollment is financially dubious.

People are worried that increasing open enrollment will cause more violence in schools and more residents to leave.

People are worried that if you mention closing schools, parents will get angry.

People worry that reducing open enrollment is in some sense abandoning children that need additional help and support.

People are worried that there won't be enough money to pay for recent raises to teacher salaries that are funded with temporary pandemic relief funding.

People are worried that the district’s quality is declining

People are worried that if you close an elementary school, then you'll need to start busing.

People are worried that if you move from the neighborhood model to the bus model then you’ll severely impair the Wauwatosa School District “brand” and enrollment will decline even further as the “neighborhood school” is now longer a draw for new residents.

People are worried that disproportionate rates of student punishment are indicative of bias and discrimination.

People worry that if you just expel students that you’re failing them or perpetuating a “school-to-prison pipeline” and not doing your duty to educate everyone.

People are worried that we can't pay teachers enough to attract new candidates.

People think we should have more specialty schools.

People think we should move administrative staff to Underwood Elementary school which is only half filled with resident students and expand the Montessori school that currently takes up half of the Fisher Administration building.

People think we should add another STEM program or expand existing ones.

People think we should close a school or two.

People think we should increase open enrollment.

People think we should decrease open enrollment.

People think we should more equitably distribute open enrollment students.

People think we need to focus more on marketing all the great things the school district offers to attract more parents.

People think we need to focus more on academic excellence .

People think we need to crack down on violence in schools.

People think we need more diversity.

People think we owe a duty to educate all children and make them feel like a part of the community.

People think we need to do more for special education students.

People think we should accept more special education students through open enrollment.

People really, really like being able to walk their children to school.

This is a lot of things, but I think you can bucket them into a few categories. Some of them—like closing a school or funding a marketing campaign—are options. They are things you could choose to do. Some of them—like concerns about inclusion, or safety or cost—are evaluative criteria. They are outcomes we care about. And some of them—like fewer young families moving to the city or the state increasing student aid—are possible futures. They are potential realities that make various options across the criteria we care about more or less effective.

People care about diversity and inclusivity, they care about cost, academic excellence, and safety, keeping “neighborhood schools,” the ability to backtrack and reverse course, and how easy or difficult something might be to sell politically. A good solution would consist of some combination of options—expand a specialty school AND distribute non-resident students more evenly AND pay for a marketing campaign—that allow the district to meet its objectives across a broad range of circumstances.

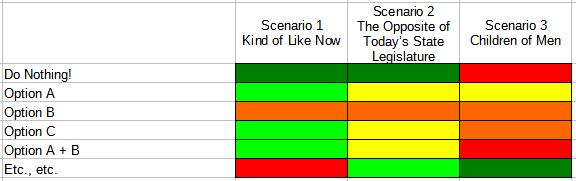

You could imagine somebody presenting—perhaps to the Superintendent or perhaps the board—a slide that synthesizes all these options or combinations of options and shows how well they are expected to perform in various situations.

The point is to provide a high-level, somewhat abstract overview of the effectiveness of various options, but if someone asks, “Well, why does this option perform so well under a scenario with declining enrollment?” there would be another slide that maybe had something like this:

And maybe someone else asks, “Well, what does Diversity/Inclusion here even mean exactly and why is it green?” and perhaps there’s another slide that discusses how things like open enrollment, school closures, and staffing placements work together to contribute to some kind of overall assessment.

And if someone else asks, “Well, how exactly do all these things combine to produce this score?” maybe you just refer them to a technical appendix or something. But ideally there would actually be answers to these questions, because all these high-level assessments of effectiveness and “goodness” would be built upon real concrete details and assumptions and estimates that are identified explicitly.

III. So what?

I skipped the hard part and just presented the final solution with a bunch of question marks and fake colors, but ideally you would work from the other direction to identify a wide range of options, estimate their costs and other impacts, select some potential futures that are meaningful and that “stress” the options in different ways. Then you could fill in the blanks of these cheesy (but I think useful) Excel charts with real results.

But working backwards does illustrate a few things. I’ll name five.

One, it is not that these tables will give you the right answer, but that the process of going through it will reveal gaps in knowledge. It forces you to be explicit about how you think the world works and how the different things people care about are related and influence one another. We might realize we don’t really understand the public’s opinion on certain issues or how distributing non-resident students more evenly across schools might affect safety or academic performance or how costly it might be or what effect it might have on resident enrollment, and you could try to estimate these things or at least acknowledge transparently that you have no idea.

Two, many board members talk about the utility of collecting data or making data-driven decisions. But one way to make data collection more efficient and useful is to know what questions you’d like to answer so that you collect the right information in the first place. Additionally, if you worry that even the mere act of collecting data will inflame public passions, one way to mitigate this is to be transparent about what questions you are trying to answer and how those answers will be integrated into some larger decision-making calculus.

Three, it makes tradeoffs explicit. One downside to traditional strategic planning or spending lots of time articulating a “North Star” is that it doesn’t force people to identify the implications of those goals or how they should be prioritized. The CFO might have a goal to balance the budget or make sure certain capital improvement projects are funded while someone else may have the goal of improving academic achievement, and you can imagine many ways those things are in tension and work in opposing directions. If the right hand doesn’t know what the left is doing, everyone can feel like they’re pursuing the right goals while actually creating problems for people in another part of the organization. For the board, agreeing on a “North Star” doesn’t really help resolve fundamental disagreements about the relative importance of different goals when resources are limited. It’s useful to clarify these things.

Fourth, you can more clearly separates facts from values. People can agree on facts and still disagree on the implications of those facts. Or people can debate facts without that debate implying that the parties involved have any particular values with respect to them.

If open enrollment students cause more fights or have lower academic performance, these are presumably facts that people could agree on while still disagreeing about how good or bad that is, how it should be weighted against other things people care about, and what, if any, actions should be taken in response to them. One person might think that we should reduce open enrollment or discipline kids more harshly and another might think that the school district should provide more support or make extra effort to help non-resident students feel like a part of the community. These opposing responses are compatible with the same reality. In some sense, they require it.

And finally, one of the more useful realizations I’ve come to in reading the great amount of research on human bias and the various ways people act irrationally, is that while it’s very hard to notice bias in yourself, it’s very easy to notice it in others. Some organizations take advantage of this by creating red teams—groups of people who’s sole purpose is to find the weaknesses in your plans and exploit them. The public, especially the members of the public who show up to school board meetings, make a pretty good red team. Sometimes they’re repetitive. Occasionally they’re unhinged. But they’re definitely helpful. And they’re especially helpful if you can use their feedback to update or refine the tradeoffs, options, and values in the framework described above.

Tradeoffs occur whether you’re explicit about them or not. From a political perspective, it might seem useful if stakeholders aren’t always aware of the downsides and implications of various choices. But I think in the long-run it probably just generates distrust and acrimony.

A real thing. Although, the more technical term is decision-making under uncertainty. One area where this applies is military planning and acquisitions. For idiosyncratic reasons, two reports I turn to again and again and that are the basis of this post are: Davis, Paul K. and James P. Kahan, Theory and Methods for Supporting High Level Military Decisionmaking. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2007. And Davis, Paul K., Russell D. Shaver, and Justin Beck, Portfolio-Analysis Methods for Assessing Capability Options. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2008.

Ben, as an engineer I love the use of excel. I completely agree with the idea of identifying the question and figuring out how to best capture the information and what specifically in the data we need to look at. Perhaps there is some good that comes from having a vision to guide you but without identifying and maybe solving some of the underlying things it doesn’t seem to make sense

Ben, I could respond in another thread but I would like to focus on the open enrollment issue before adding a second comment about other issues raised by you in this post.

It is natural for people to ask why there are more OE students in particular schools. They asked similar questions when the chapter 220 program originated. To make sense for either program, a suburban district would not accept additional non resident students for a school if it meant that another section would have to be created in that school which would mean hiring an additional teacher. It would seem that this would be a more important concern now since there were no state imposed revenue limits when the chapter 220 program started. In your summary on open enrollment, Dr. Means seemed to talk about this when he discussed Wilson school.

When you look at the location of the majority of elementary schools with a higher percentage of OE students, they are located on the south side of the district. It would seem to be impossible to move some of the OE students in those schools to the four elementary schools located north of the village and east of the parkway without causing an increase in class sections in any of these schools. That would seem to be a non starter for a variety of reasons. I am sure that there are additional reasons why this issue is occurring.

One other quick point. There seems to be some belief that people are leaving the district because of this issue and several others. You indicated that there did not seem to be any reliable information indicating that this was true. Let me give you one data point that I hope indicates something different.

When I sold my house in Wauwatosa after living in it for 42 years, the main reason people gave for wanting to buy my house was that they wanted to move there so their children could attend the Wauwatosa schools. I hope things have not changed in the last few years.