As a reminder, I am currently traveling and this will be the only newsletter this week.

There was a School Board meeting on Monday. They covered everything from the renewal of the annual HVAC service agreement (cost: $44,000) and a presentation of the proposed 2022-2023 budget (more details next week), to appointments for the board’s subcommittee on Legislative Advocacy (nominations: Board Members Leigh Anne Fraley and Eric Jessup-Anger).

But they also touched on the same theme that has run through many months of School Board meetings: the district’s response to increasing violence and behavioral problems in schools.

I previously quoted an exchange from the May 22 meeting of the School Board regarding a policy that students involved in fights would be issued citations by the police. Board Member Jennifer Hoag said:

I do want to ask a question about the citations that has been raised as a concern by some of our community who are worried about creating a school-to-prison pipeline. Where we're creating arrest records or citation records for students for things that are happening in the school building.

To which the school district’s superintendent, Dr. Demond Means, responded by noting that this is a pretty standard response to incidents of violence in other school districts he’s worked at, and while he is conscious of the “school-to-prison pipeline”, he is “more sensitive to families who have shared with me that their children are afraid to go to school.”

Discipline in schools was briefly addressed again on Monday, mainly to highlight that the Superintendent would hold listening sessions on June 15 and June 201 for community members to talk about the school’s proposed framework for handling discipline problems going forward. Superintendent Means said:

This disciplinary framework that I want to discuss and collaborate with community members around, not only lays out the consequences in a very clear way, but also lays out our resources around social, emotional, and mental health. It lays out opportunities for us to restore students through restorative circles and having the opportunity to discuss how they have violated the rules and how they hurt the school community and how the school community will be there to support them to make better decisions in the future. That feels more like a comprehensive approach to school safety and school discipline that we are intending to implement next year.

What is a “restorative circle”? What is the “school-to-prison pipeline”? I thought it might be useful to provide some of the context and background behind what he is describing here, mostly because it was unfamiliar to me and I assume may be unfamiliar to others.

II. Background

Suppose a teacher sees a student in the hall using a cell phone in violation of this particular school’s rules. She confronts the student and the student begins yelling at her to mind her own business, or get out of his face, or something. An administrator is summoned, and because this same student has had a number of similar incidents in the recent past, tells the student that he can’t play in tonight’s basketball game and that he’ll be suspended as well. The student, angry, returns to the teacher’s classroom, interrupts class, begins cursing and accusing the teacher of lying about his behavior to the administrator, and, as some friends try to shuffle him toward the door and out of the classroom, he picks up a desk and flips it over. What’s the right response here?

This is essentially the scenario described in a New York Times Magazine article from 2016. The article is sort of a long meditation on potential answers to this question but also delves into a lot of the competing personalities at this particular school which I don’t necessarily care about. So I’ll be a little more abstract.

There are, as far as I can tell, two competing models for how discipline problems in schools should be handled.

In the first model, students who break rules are told to stop breaking the rules right now and then some type of punishment is meted out based on the severity of the offense and the age of the student. These punishments are codified in a conduct manual, and teachers and administrators have relatively little discretion in deviating from these stated policies.

Maybe the student is made to apologize, but this isn't really an integral part of the process, and mostly the punishment is meant to act as some combination of (1) deterrent—the perpetrator and others aware of the punishment don’t want to face a similar punishment in the future and so refrain from the behaviors that lead to it, (2) incapacitation—the offender is removed from the situation so that they can no longer physically continue breaking the rules in the way they have been, and (3) retribution—although not typically an explicit goal, the punishment can make the victim feel that justice has been served and even absent any deterrent effect, there is a sense in which many feel a punishment is still “deserved.”

You might call this the zero-tolerance model.

In the second model, the student is seen as part of a community. Actions that violate the rules have in some way placed him outside the community, and it is the community’s job to tell him how his actions have hurt them and what he can do to become an accepted member of the community again. They may be educated on better ways to handle their emotions, forced to sit in a circle and speak with victims to understand how his actions made them feel, and perform some type of community service related to the infraction. If he destroyed a teacher’s classroom, he might help her clean it. If he spray painted a wall, he might help the custodian repaint it. In this model, punishment is meant to act partly as (1) rehabilitation—learning behaviors that will make them less likely to get in trouble in the future, and (2) restoration—repairing the relationship between the offender and his victims and the community he is a part of.

You might call this the restorative justice model.

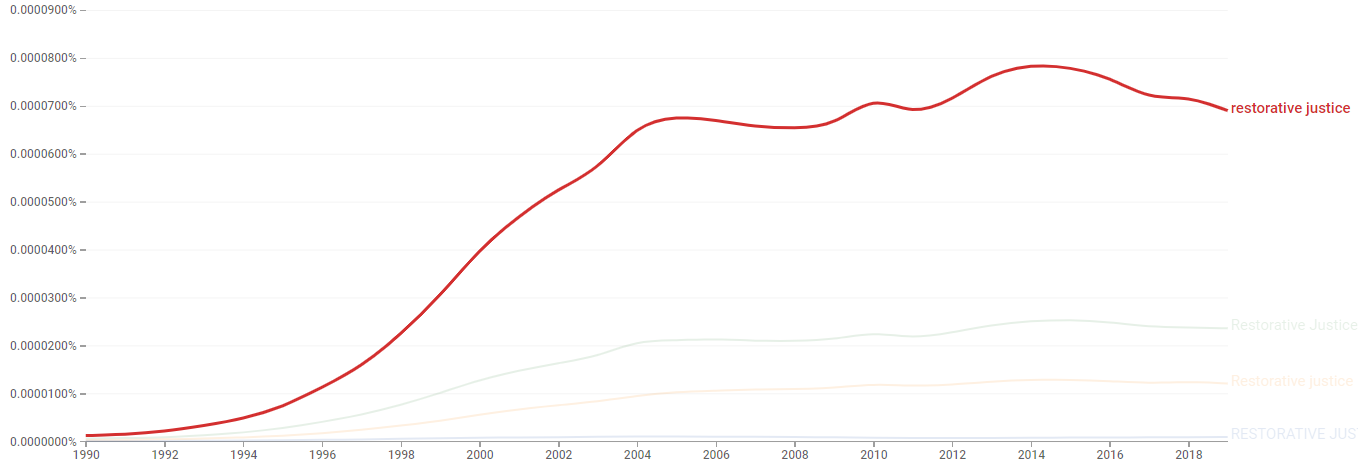

The second model has become particularly popular over the 15 years, partly as an attempt to reverse some of the pernicious effects of the first model.

The zero-tolerance model is an outgrowth of various tough-on-crime policies instituted within the United States during the 1980s and 90s when crime rates were much higher. While crime subsequently began declining from the early-90s until about 2014, it also led to a huge increase in the prison population and worries that minorities, mainly African Americans, were being unjustly imprisoned since they comprise only 13% of the U.S. population but comprise a much larger percentage of the prison population.

In schools, zero tolerance policies led to lots of dumb-sounding overreactions by teachers and administrators where 6-year-olds were suspended for making a gun-shape with their index finger and thumb, or throwing temper-tantrums, or doing something else that seemed pretty normal for a 6-year-old to do. Many were also concerned by the fact that students with disabilities and black students were being suspended and expelled at much higher rates than their white peers. They worried that suspensions removed the kids from a a supervised learning environment, making it more likely that they would lose interest in school, drop-out, commit crimes, and find themselves in prison. This was termed the “school-to-prison pipeline”, and in 2014, President Obama threatened schools that had large racial disparities in suspension rates with a loss of federal funding for violating anti-discrimination law.

One way that schools have tried to address these disparities is through changes to the disciplinary system. Instead of ejecting offenders from the school community, restorative justice practices try to find ways that they can be reintegrated.

The District’s Superintendent frequently talks about creating a community that everyone can be a part of, that “There are no bad students. They just make bad decisions once in a while,” or that, “we welcome all students, but we don't welcome some of the behaviors that we've been seeing this year.” There is some sense in which statements like these are sort of intuitively understandable, but I think there’s another sense in which they are firmly grounded in this relatively new restorative justice model of punishment and discipline.

And if you read some of the promotional materials for different restorative justice programs, it sounds revelatory. For instance the International Institute for Restorative Practices has a SaferSanerSchools program that promises, I think, to solve almost every long-standing problem that schools encounter:

For members of the community, outcomes include:

Improved relationships between school-based staff and students

Improved student to student relationships

Improved work climate and employee engagement

Improved relationships between school-based staff and families

When a school community consistently and sustainably implements restorative practices, a stable, positive school climate develops with the following potential benefits for ALL students:

Lower suspension and expulsion rates

Reduced discipline disproportionality for marginalized students

Increased positive youth development and social-emotional learning

Stronger sense of school connectedness

Improved student well-being

Improved behavior and absenteeism

Increased academic achievement

III. Does it work?

There is a frustratingly common progression when it comes to social science-based public policy interventions. Something is tried at a relatively small-scale—in a village, or at a single school. The program or intervention sees significant success, improving whatever is being measured by some unbelievable (but everyone still believes it) percentage. There’s a lot of enthusiasm from the public, and a lot of, This is the solution we’ve been waiting for. Hundreds of millions or billions of dollars flow from charities and the government to expand these programs to other villages, schools, states, and countries. If it works for a couple hundred people, surely it will work for a couple million.

For example, internationally, people got really excited about deworming children in Africa because a study done in Kenya in the late-90s found that giving students deworming pills improved health, cognition, and school attendance by some large percentage. People decided this was the key to unlocking prosperity in Africa, started pouring money into deworming initiatives in other areas, and ultimately saw very few of the large effects touted in the original study.

Closer to home, educational interventions like Head Start and other Pre-K programs saw huge increases in funding based on the wild success of a few small-scale studies. Support for universal pre-K remains a significant policy priority up to today even though hundreds of further, much-larger, much better designed studies find negligible results.

In Texas, testing students each year and rewarding those schools that raised test scores with increased funding produced the Texas Miracle that inspired George W. Bush so much that he rolled out the No Child Left Behind Act nationwide. An Act which almost everyone hated, generated very few of its supposed benefits, and which was itself eventually Left Behind in 2015.

My guess is that a similar sequence is probably at play when people talk about instituting restorative justice principles in schools to narrow the racial achievement gap, eliminate the “school-to-prison pipeline,” and reduce racial bias in school discipline.

Because we try lots of things. And it almost never works.

There have been many studies touting the beneficial effects of restorative justice. But these studies are often either small, not really designed to tease out the causal effects of restorative justice policies in schools, or don’t actually deal with restorative justice at all. For instance, the list I quoted above of all the positive effects of restorative justice practices provides supporting citations for the last seven.

Lower suspension and expulsion rates? This RAND study cited in support was actually pretty good. We’ll come back to this one.

Reduced discipline disproportionality for marginalized students? The cited study involved 29 teachers across two schools and 400 students who volunteered to take a survey. (Article)

Increased positive youth development and social-emotional learning? The cited study was a qualitative analysis of 14 interviews with teachers across six schools and six focus groups with a total of 40 students. (Article)

Stronger sense of school connectedness? This actually seems to be a study of the relationship between positive perceptions of school climate and bullying in schools that practice “Restorative Practices” (RP) but doesn’t compare it to schools that do not practice RP so it seems difficult to know what effect the restorative practices are actually having. (Article)

Improved student well-being? The cited study is a literature review that doesn’t mention restorative justice at all. (Article)

Improved behavior and absenteeism? This article also does not mention restorative justice anywhere. (Article)

Increased academic achievement? The cited article doesn’t mention restorative justice anywhere. It is a survey of about 3,400 student in 5 schools looking at whether things like grades correlate with measures of school climate. (Article)

Similarly, the Wauwatosa School District in a document outlining how they will use $50,000 in emergency relief funds provided by the federal government, proposes restorative justice training for counselors, social workers and administrators. As evidence for the benefits of this program they cite a 2015 article by Guckenburg et al. “Restorative justice in U.S. Schools: Summary findings from interviews with experts” and a 2016 article by the same authors called “Restorative justice in U.S. schools: Practitioners’ perspectives.”

But these are just interviews and surveys of individuals who implement restorative justice practices about how they do it and challenges they’ve faced. The evidence consists of statements like “According to survey results of practitioners implementing restorative justice, a majority (54%) indicated that the practices were successful.” It’s not nothing, but it is just, like, your opinion, man. Kind of like asking your financial advisor if its a good idea to give him your money. How do they know it was successful? Or that something else wouldn’t have been equally beneficial?

The best way to understand whether things like restorative justice really work is to randomly assign some group of people to try it out and another group to continue doing whatever they were doing—suspending people, calling the police on 6-year-olds, etc. This is the essence of a randomized controlled trial (RCT).

An RCT takes a sample of people and randomly assign half of them to receive a treatment (in this case a restorative justice program) and the other half to act as a control (i.e., don't change anything they were doing). Ideally you have enough people in the random assignment pool that differences between individuals in the treatment and control groups roughly balance out.

For instance, suppose you wanted to see whether some new medication reduced the risk of heart attack. You randomly assign one group of people to get the medication and the other group to get a placebo. However, it would be bad for the average age of the group receiving medicine to be 56 while the average age of the control group is 30. Older people are more likely to have heart attacks, and so even if the medication worked, you might not notice it because the control group was so much healthier. With a large enough random sample, these kinds of differences should roughly cancel out. If you have a big enough group of people and the average age of that group is 40 years old, the treatment and control groups should both have an average age of roughly 40.

The same applies for characteristics like gender, pre-existing conditions, BMI, and whatever else might be correlated with heart attacks.

And there have been a couple studies like this. But not a lot. I’ll mention two.

Cochrane Review

The first was actually a systematic review by Cochrane of all the RCTs done up until 2013 where restorative justice conferencing was used to reduce recidivism among young offenders (in the review, ages 7-21). Out of the hundreds of studies they considered for their review, there were really only four that were considered rigorous enough for inclusion. These were randomized or quasi-randomized controlled trials that included a total of about 1,500 young offenders . They found that:

Results failed to find a significant effect for restorative justice conferencing over normal court procedures for any of the main analyses, including number re‐arrested, monthly rate of reoffending, young person’s remorse following conference, young person's recognition of wrongdoing following conference, young person's self‐perception following conference, young person's satisfaction following conference and victim's satisfaction following conference. A small number of sensitivity analyses did indicate significant effects, although all are to be interpreted with caution.

The authors conclude:

There is currently a lack of high quality evidence regarding the effectiveness of restorative justice conferencing for young offenders. Caution is urged in interpreting the results of this review considering the small number of included studies, subsequent low power and high risk of bias. The effects may potentially be more evident for victims than offenders. The need for further research in this area is highlighted.

RAND’s Study of the Pursuing Equitable and Restorative Communities (PERC) program in Pittsburgh

The second is a randomized control trial of restorative justice practices conducted by the RAND Corporation and detailed in their report from 2018.

RAND conducted an RCT of the SaferSanerSchools program mentioned earlier by implementing it in a subset of Pittsburgh schools and comparing outcomes against another subset of schools that carried on with business as usual. The Pittsburgh Public School System (PPS) included 46 of its 56 schools in the random assignment. The ten that were excluded were excluded for a bunch of reasons that all seemed reasonable and legitimate (one school is an online academy, some schools served only special-needs students, etc.)

To minimize the differences between the treatment and control groups, the researchers actually ranked all the schools based on a number of factors including rate of suspensions, measures of classroom management effectiveness, and measures of student conduct. They then took pairs of schools that were very similar along these measures, put one in the control group and one in the treatment group and did this for each of 23 pairs of schools.

They then looked at the effect of the restorative justice intervention over two years by measuring suspensions, arrests, absences, how many kids leave or transfer out, academic achievement, and student and teacher perceptions of discipline and behavior.

The summary includes several positive things that they found:

Improved school climate, as rated by teachers,

Greater decreases in suspension rate among schools implementing restorative practices, although it wasn’t huge. (From the report: “PERC reduced the number of days lost to suspension per student during Year 2 by 0.10 from what it would have been in the absence of the PERC initiative. The baseline number of days lost per student in the treatment and control schools was 0.63 in 2014–15, so this equates to a 16-percent reduction in days of instruction lost to suspension”)

Lower suspension rates for low-income and African American students, reducing disparities between white and high-income students,

However, they also mentioned that they found:

No improvement in academic outcomes, with students in grades 6–8 actually doing worse, and

No decrease in arrest rates.

And there were other things buried in the report. For instance, that the program “had a negative impact on achievement for both African American and white students at schools that were predominantly attended by African American students,” and that while teachers thought the school climate had improved, the student’s own ratings of their teacher’s classroom management and the classroom climate was significantly lower.

I think it’s hard to say whether the benefits are worth the significant amount of time and training it takes for teachers and students to sit around in circles talking about their problems rather than sending a disruptive student to the principal and getting back to teaching.

As the University of Chicago economist John List explains, most things don’t scale because:

There are lots of false positives and for many reasons. Someone might have made an error in their analysis, but sometimes the reasons are more pernicious. Researchers are more likely to tout their successes (and get more media coverage of them) than their failures. And small studies are just statistically more likely to have exaggerated effects.

The population where the intervention worked might be very different from the population you’d like to scale that intervention to.

Some elements essential to the success of an intervention (like talent) cannot be scaled easily.

There might be negative unintended consequences that don’t appear at small scales but do at large scales.

Dis-economies of scale. Some things become more expensive as you scale them rather than less.

Maybe $50,000 for a Restorative Justice Steering Committee or $500,000 for behavioral specialists to implement restorative justice practices isn’t a lot of money (and the behavioral specialists are presumably useful even if they aren’t conducting restoration circles). And it definitely seems as if the school district is not abandoning one model and embracing the other but instead charting some more reasonable middle-course. But I think we should still be more skeptical of rosy-sounding success stories, because the success of most interventions and big new ideas just doesn’t replicate. And if the idea that all your kid needs to do to stop being bullied is sit in a circle with his tormentors and tell them how badly it makes him feel seems too good to be true, it probably is? Maybe you could get more benefit by putting that $50,000 toward the HVAC system?

Thanks again for a most comprehensive report.. Your idea that a hybrid between the restorative justice and the old style handling of disciplinary problems seems like a good one, but, as we know, if everyone isn't treated the same, there will be discrimination charges by someone. The causes of disciplinary problems are many. Unfortunately, there's no magic bullet to address them. We need only look to the lust for violence and the feelings of hatred shared by many in our society to realize where some of these disciplinary problems arise. Empathy has disappeared from our society.