Try some more. The strawberries taste like strawberries. The snozzberries taste like snozzberries!

I.

This article isn’t really about development (or snozzberries for that matter), it’s about the tax exempt status of nonprofit hospitals, but I mention it briefly as a lead-in. Many people get upset when large commercial and residential buildings go up next to their single-family homes. They had a nice life where they could see the sky, plant their garden in full sunlight, and observe quiet, residential streets, and now they worry that an air conditioner might fall on their head.

For those that would like to see more large residential and commercial buildings, one argument is that it is otherwise difficult to raise revenue. Due to complicated state laws that constrain how much freedom local governments have to set their own tax rates, one of the few ways to increase city revenue is through new construction and the ensuing increase in property taxes that such construction brings. This is an interesting topic on its own, but I want to focus on who pays property taxes, and also who doesn’t.

When I divide my property tax bill from last year by the assessed value of my home, I get a tax rate of 2.0%. This includes not just what the city charges, but also taxes for the school district, the Milwaukee Municipal Sewage Department, and the Milwaukee Area Technical College. The City of Wauwatosa itself taxes property at a rate of $7.00 per $1,000 of assessed value, or 0.7%. This varies year-to-year because the city doesn’t actually set a tax rate, they pass a budget, and whatever sum of money is required to balance that budget after accounting for other sources of revenue like fees, fines, and permits determines the property tax rate. Overall, about 73% of the city’s revenue comes from property taxes. In 2022, this came out to $48.7 million dollars in property taxes on land with a total value of $7.1 billion dollars.

But not everyone wants to pay as much in property taxes as the city thinks they’re owed, and some do not want to pay any property taxes at all. When someone doesn’t like their property tax bill, they file an objection with the Board of Review which most recently met on May 19th. Some highlights:

The city thinks the Lowe’s home improvement store on 12000 W. Burleigh St. is worth $14.35 million but Lowe’s thinks it’s only worth $7.1 million. Apparently, this disagreement has been going for years and they’re not budging on this $7.1 million figure.

The Target at 390 N. 124th St. got taxed based on an assessed value of $16.9 million but Target thinks their property is only worth $11.6 million. They’ll probably sue the city too.

The Aurora Health Center on 2999 Mayfair Rd. bought their property in 2018 for $28.8 million. Funnily enough, that’s what the city thinks the property is worth. But the owners say it’s actually only worth $12.2 million. They’re suing the city.

But this is pretty small change. The businesses with the most at stake are Froedtert Memorial Lutheran Hospital and closely-related Froedtert Health, the Medical College of Wisconsin, Children’s Hospital, and the Milwaukee Regional Medical Complex (MRMC) Land Bank which from what I can tell—based on this article and this document which I didn’t really read but skimmed—is a separate partnership among these same organizations created to purchase land that they previously leased from Milwaukee County.

The assessed value of all these hospital-related properties is $677 million dollars. At the property tax rate of 0.7%, $677 million dollars of property would produce about $4.7 million dollars in tax revenue. That’s about 10% of the City’s total revenue from property taxes and almost 7% of the city’s total budget of $70 million.

But Froedtert and the Medical College and Children’s Hospital say their properties are only worth, at most, a total of $45 million. And that’s being kind of generous, because they really think they’re worth $0—at least for tax purposes—and therefore they shouldn’t be paying any taxes at all. When 10% of the land by value is owned by companies that don’t pay any taxes on it, homeowners and other property owners pay more. One way to think of it is that if the property tax you pay to the city (not the total property taxes) are $2,000, maybe it’d be closer to $1,800 if these hospitals also paid taxes on the property they owned.

II.

So why do these hospitals think they don’t need to pay taxes?

It’s likely that if you know one thing about the difference between for-profit and nonprofit businesses, it’s that the latter get some kind of tax benefit. They’re often tax-exempt at the federal and state level from income taxes. And they’re frequently tax-exempt at the local level from property taxes as well.

Wisconsin Statute 70.11 lists lots of things that are exempt from property tax.

The list includes everything from state-owned or city-owned land to colleges and universities to…manure storage sheds, art galleries, cemeteries, bible camps, nonprofit radio stations, Lions foundation camps for children with visual impairment, and my favorite for it’s extreme particularity “Vacant parcel[s] owned by a church or religious association [if they are] no more than 0.8 acres and located in a 1st class city, that is less than a quarter mile from the shoreline of Lake Michigan, and that is adjacent or contiguous to a city incorporated in 1951 with a 2018 estimated population exceeding 9,000.” And of course, in subsection 4, the state exempts “Educational, religious and benevolent institutions; women's clubs; historical societies; fraternities; libraries” including, per sub-subsection (m), “Nonprofit Hospitals."

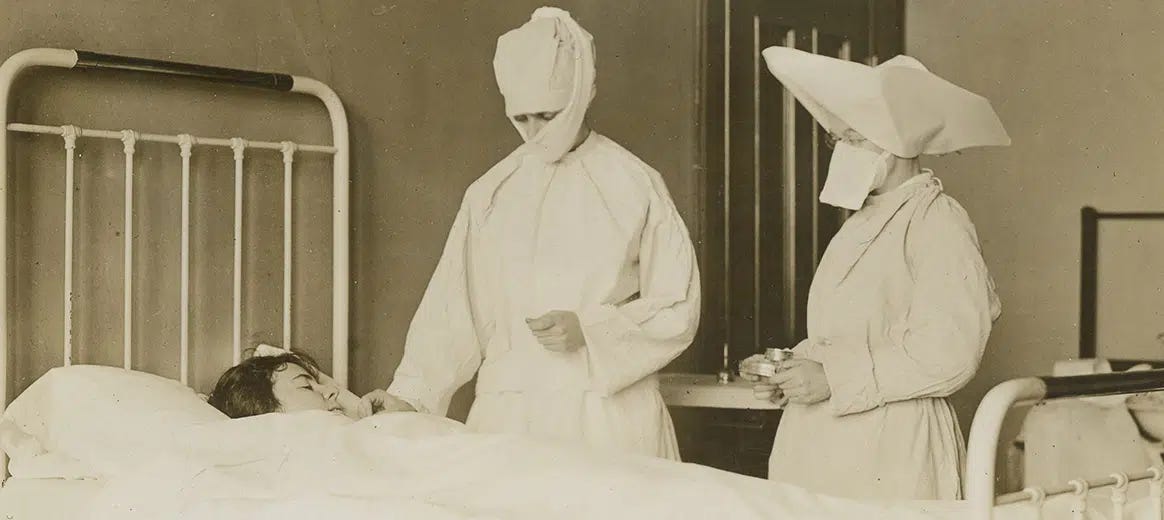

I think the intuitive case for exempting such buildings from property taxes is that they serve some sort of pro-social, altruistic goal, and it is good for the government to encourage such things (by making them cheaper to do). It’s right there in subsection 4: benevolent institutions. The term itself feels sufficiently archaic that it evokes images of nuns in nursing caps tending to the maimed and indigent:

More recently (since 1969), the idea behind exempting nonprofit hospitals from various taxes is not just that they are being altruistic or pro-social but that, more narrowly, they provide some sort of community benefit. We agree not to tax you, the government says, and you agree to provide services to the surrounding community that it would likely cost us more to do ourselves.

III.

It turns out that nonprofit hospitals really care about proving they are benefiting the community. They care less, it seems, about actually benefiting the community, but we’ll get to that.

For example, in the early 1990s when the Wisconsin state legislature formed a task force called the Special Legislative Council Committee on Property Tax Exemptions to see whether it was worth continuing to provide these benefits and potentially recommend alternatives, the Catholic Health Association of Wisconsin—who operate various nonprofit hospitals in the state—teamed up with the Wisconsin Hospital Association to form their own counter-task force called the Task Force on Social Accountability. The goal of their task force was to convince Wisconsin state representatives that “Yes, you should continue exempting us from taxes, and these other ideas you’re hearing about are terrible.”

The Catholic Health Association even wrote a book (unfortunately, sold out on Amazon) called Social Accountability Budget: A Process for Planning and Reporting Community Service in a Time of Fiscal Constraint and their most recent guide, helpfully updated just a few months ago, is called Community Benefit and Tax Exemption: A Guide to Talking to Media, Policy Makers and the Public. Just in case people start asking questions.

But what I think these dueling task forces suggest is that it was becoming harder to distinguish between nonprofit and for-profit hospitals. For example, which of these two hospitals is a nonprofit?1

Another puzzle: despite an adjective suggesting the complete opposite, nonprofit hospitals do make profits.2 And those profits can be pretty decent. Froedtert Memorial Lutheran Hospital had a net income in 2020 of $143.6 million on $1.96 billion in revenue which gives it a profit margin of 7.3%. It’s profit margin in 2019 was 6.4%.

For comparison, Tenent, one of the largest publically-owned for-profit hospital operators in the United States had a profit margin in 2021 of 4.9%. HCA, another large publically-owned for-profit hospital operator, and the owner of the Dallas hospital in the top picture above, had a profit margin in 2021 of 11.4%

I admit I was surprised by this. My guess was that if the explicit goal of your business was to make a profit, you would do better at profiting than a similar business who did not have that goal. One explanation that I can think of is that it is easier to profit when you are not paying taxes.

Okay, you say, nonprofit hospitals might look the same as for-profit hospitals. They might even be similarly profitable. But obviously they’re more altruistic, more pro-social, and more beneficial to the surrounding community, right?

This was actually so unobvious that in 2006 the IRS decided nonprofit hospitals needed to start writing down all the ways they were benefiting the community and how much these benefits were worth. This is known as Form 990 Schedule H. The Congressional Budget Office and Government Accountability Office produced various reports trying to understand the same thing. What are these nonprofit hospitals actually doing that is worth the tens of billions of dollars in tax subsidies they’re being given?

In Froedtert’s case at least, and according to their Schedule H, 12.5% of their expenses—$227 million dollars—went toward community benefits in 2019. But when you look closely, the vast majority of this $227 million dollars comes from two things:

→ Medicaid Shortfalls. Some health insurers will reimburse hospitals a lot for a procedure and some insurers are more stingy. They might reimburse hospitals less for a procedure than it actually costs the hospital to provide. One of the stingiest insurers is the federal government via Medicaid. The difference between Medicaid reimbursement rates and the cost of treating Medicaid patients is called “Medicaid shortfall.” Hospitals could potentially refuse to treat people with Medicaid because their reimbursement rates are too low. Or they could accept Medicaid patients, eat the cost difference, and use that fact to justify their tax-exempt status. For Froedtert this Medicaid shortfall amounts to $120 million, or 53%, of it’s community benefit.

→ Education. The other major portion of Froedtert’s community benefit is the $87 million spent on education for health professionals. This includes medical students, interns, residents, fellows, and nurses. While I agree that this is a good thing and certainly beneficial to America as a whole, it’s harder for me to see the benefit to the community in particular. Don’t most doctors go somewhere else after their training is complete?

In contrast, charity care (called Financial Assistance at Cost by the IRS)—the original justification for tax exempt status until 1969—accounted for only 0.5% of expenses, or about $8.4 million dollars.

IV.

While it’s nice that nonprofit hospitals provide these community benefits, it turns out that for-profit hospitals also cover medicaid shortfalls, spend money on educating nurses and doctors, and provide charity care.

A 2017 study by Bai, Zare, and Hyman compared for-profit hospitals and nonprofit hospitals around the country and found that both spend similar amounts covering shortfalls in Medicaid reimbursements. And Herring, Gaskin, Zare, and Anderson have argued that it’s not even clear why Medicaid shortfalls should be considered a community benefit since the IRS does not count similar shortfalls from Medicare or other commercial insurers.

If both for-profit and nonprofit hospitals provide these community benefits, what actually matters is not the absolute value the nonprofit hospital provides but the incremental community benefit it provides beyond what a tax-paying for-profit would.

In that same Herring et al. study, the authors find that nonprofits do indeed offer more community benefits than for-profit hospitals, but it’s not that much more. And while, on average, a nonprofit hospital provides an incremental community benefit that exceeds its tax-subsidy, 62% of nonprofit hospitals do not. They offer this conclusion:

For policymakers who desire to motivate hospitals to provide adequate community benefits and, in particular, sufficient charity care to underserved populations, the tax exemption currently appears to be a rather blunt instrument, as many nonprofits benefit greatly from the tax exemption yet provide relatively few community benefits.

I’m not sure if Froedtert and its affiliate hospitals soak up more in tax subsidies than they provide in benefits. The studies above just provide averages, and any individual hospital could be better or worse. But I did find it interesting that a nonprofit business sitting on 10% of the city’s potential property-tax base doing pretty much the same thing as a for-profit business and making about the same amount of money doing it, nevertheless gets several million dollars in tax subsidies for it.

It’s the second.

They just can’t distribute them to shareholders or use them to reward executives. While many for-profit companies also do not distribute dividends and invest net income into expanding their business, it does seem that this restriction on pay is limiting: Froedtert’s CEO makes about $2.6 million compared to a median CEO pay for publically traded companies of about $20 million.

This is very interesting. With the cost of health care these days, it seems that there should be some equity in these institutions paying their fair share of taxes. I don't think poor people can be served at Froedtert, except in emergency situations. As soon as the emergency is over, that's the end of the treatment. Don't know about other hospitals. (Non-profits).