Auditor reports on City's 2021 finances

Yes, the audited financial statements were late but everything is peachy, okay?

I.

Did you know that the city of Wauwatosa has outstanding ambulance billings of $1,069,038 which it has so far been unable to collect?

Or that it makes almost $400,000 per year renting the tops of its water towers to cell phone companies to place antennas on?

That in 2021, the city’s top employer—the Milwaukee Regional Medical Complex—employed 14 times as many people as it’s second largest, the recently bankrupt Briggs and Stratton1?

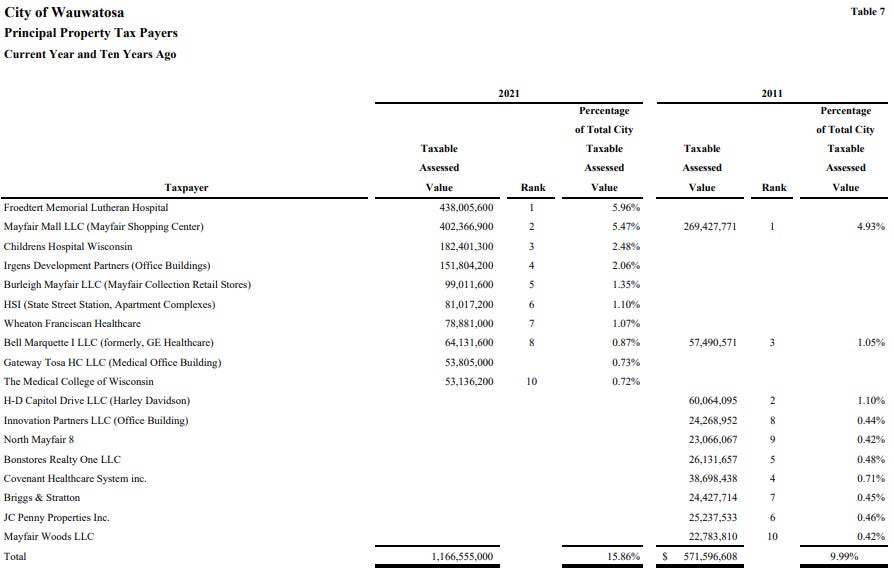

That the top taxpayer, Froedert Hospital, comprises 6% of the city’s tax base and its second biggest taxpayer, Mayfair Mall, 5.5%?

Or that for some reason the city sold 10x as much water in 2021 as it did in any other year going back to 2011? What’s going on there?

Or that Wauwatosa spent an enormous amount of money on Conservation and Development in 2015? What was that for?

These are only some of the exciting things you can find in the city’s recently audited 2021 financial statements. But I think the better question to ask is: if a city was heading toward bankruptcy2 or was just terribly mismanaged, how would you—as a random citizen with no real financial expertise—know?

Fortunately, as a random citizen with no real financial expertise, I can try to answer this.

II.

I suppose at some level you should just be able to take a look around and see that potholes in the road were never fixed, or the city could only pay its employees to work four days a week, or that it wasn’t always certain water would come out of the tap when you turned it on the bathroom faucet in the morning. Maybe you lived in Detroit circa-2012 and the simple act of walking out your door in the morning was all the evidence you needed.

But sometimes the situation is less like Detroit and more like Stockton, a city in California’s Central Valley where everything seems like it’s going really well—employees are well compensated, home values are chugging upwards, there are plans to build a marina, a new city hall, a sports arena slash concert forum, etc.—and then the tide turns, the economy goes south, and “Oh wait, we can’t actually afford any of those things.”

But you’d probably hope to know before it got that bad. When there was still time to fix things or at least complain to others that they should fix things.

You’d want employees and elected officials in city government to tell you themselves when cuts needed to be made or just refuse to consider whatever zany and fiscally imprudent idea residents came to you with that day. But maybe they’d also worry that if they pushed back too much they’d lose a reelection or get fired, and so they don’t emphasize the negative things that are going on and mostly just tell you everything’s great, nothing involves difficult tradeoffs, and there are no downsides to anything ever.

People have thought of this—that the incentives for employees and elected representatives in government are not always perfectly aligned with the public’s and may also include concerns about keeping their jobs or trying to be seen as doing something impressive that can bring a lot of short-term esteem and goodwill even if it causes problems for everyone else long after they’ve retired. And so many cities, just like publicly traded companies, are required to have their financial statements audited by a third party. That third party could be any public accounting firm, maybe even one of the “Big Four” like PricewaterhouseCooper, Ernst & Young, Deloitte, or KPMG.

But sometimes those guys are not always so helpful either. The “Big Four” were actually the “Big Five” until 2002 when Big Number Five Arthur Andersen imploded after its client Enron—ranked one of the “100 Best Companies in America” by Fortune magazine—was revealed to be a massive fraud and that the auditors had helped them cover it up. It turns out that when one part of your business is auditing and the other part of your business is providing consulting services to those same companies, being too uptight about the former makes companies not want to hire you for the latter. So auditors too do not always have incentives perfectly aligned to benefit of the public.

Of course, the city’s finances are also scrutinized by ratings agencies, like Standard & Poor’s or Moody’s, to determine how likely they’ll be to pay back the money they borrow. When a business or a city needs to take out a loan, the people who buy that debt depend on the ratings agencies to look at the financial health of the city and give it a credit rating that accurately reflects the risk to potential bondholders. The greater the risk, the higher the interest rate they’ll demand.

Presumably if Moody's got this wrong too often bondholders wouldn’t trust them and they’d go out of business.

And yet…they in fact did get things pretty wrong in the years leading up to the financial crisis in 2008 where they rated lots of mortgage-backed securities as the safest of all possible investments even though they were not safe at all and contributed to one of the longest and deepest recessions since the Great Depression. It turns out that when a company or a city pays you to rate their bond offerings, you have some incentive to help the customer get the lowest interest rate possible even if an objective assessment of the facts might suggest something higher better reflects the underlying risk.

Stockton, the city mentioned earlier, filed for what was then (in 2012) the largest municipal bankruptcy in history. One person interviewed in this article described the city’s financial problems as a “slow-moving train wreck” that had been over fifteen years in the making. Yet, from the same article, ratings agencies remained “quiet about any risks and only started to downgrade the city’s creditworthiness two years [before its bankruptcy].”

So it is at least sometimes worth being skeptical or trying to look at things more closely, even if you are not an expert and even if all the experts say everything is great. And of course, sometimes after looking at things, you end up mostly agreeing with all the experts, and that’s okay too.

III.

Last week, on November 29, Wauwatosa’s Finance Director, John Ruggini, along with a representative from the city’s long-time auditing firm CliftonLarsonAllen (CLA) reported results from an audit of the city’s 2021 finances.

“This is somewhat unusual,” Mr. Ruggini said, by way of introduction, “that we’re this late in the year presenting the audit. Typically this would be done in June or July. But there were a lot of factors causing us to be this late."

Factors which he did not really elaborate upon but which may have been related to delays caused by a change in accounting software.

Nevertheless, by all accounts, the City of Wauwatosa is in great financial shape.

Jake Lenell, the partner from CLA said things that I would consider effusive praise coming from an accountant like, “there are no significant matters to note” and “the information that your management team [and] your finance team is preparing is sound” and “you continue to be a low-risk auditee.”

If you compare Wauwatosa to a city like Stockton, this all seems like it’s probably pretty accurate. In Stockton, expenditures for public safety, police and the fire department consumed 77% of the budget, they had taken out massive amounts of debt assuming property values would continue to increase like they had in the early 2000s, and they were happy to lavish handsome pension benefits on municipal employees. In one case, a guy had only worked there for a month before he became eligible for uncapped lifetime health benefits.

None of these things apply to Wauwatosa.

When I asked Google, “How would you know if a city was headed for bankruptcy?” it helpfully provided this article, written following Detroit’s bankruptcy, that said:

Top 10 Warning Signals To Determine Bankruptcy Candidates

Management Credit Risk Factors:

1. Late budget adoption, or late receipt of audited financial statements

2. High degree of senior administrative turnover

3. Government showing lack of willingness to support the debt

Economic Credit Risk Factors:

4. Unemployment rate over 10%

5. Income level that is less than 75% of U.S. average

6. Tax base market value that is less than $50,000 per capita

Debt Credit Risk Factors:

7. Total debt service that represents more than 25% of expenditures

8. Unaddressed exposures to large unfunded pension or OPEB obligations

Financial Credit Risk Factors:

9. Limited capacity or willingness to cut expenditures

10. Overall general fund balance of less than 1% of expenditures, or general fund deficit

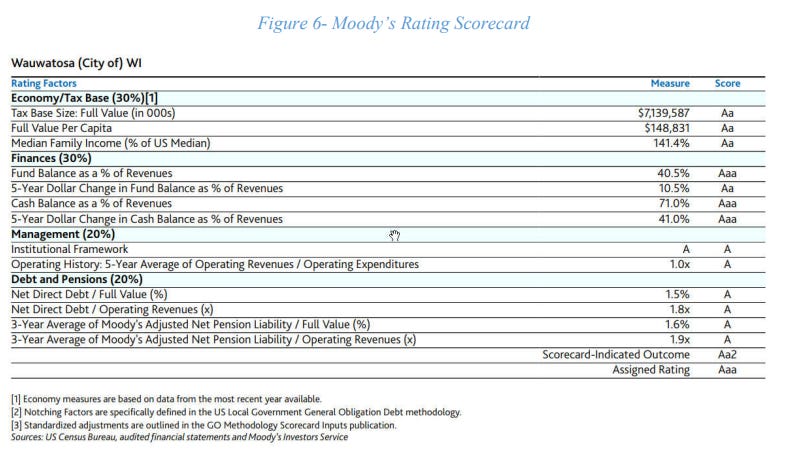

Other than the first one (Oops!) none of these things seem to apply. Mr. Ruggini has been been the Director of Finance for 12 years (#2), and the unemployment rate in Wauwatosa is 3.2% (#4) compared to the state’s 5.4% and Milwaukee County’s 6.5%. According to the Moody’s scorecard, the household income of Wauwatosa residents is 41% above the median3 (#5), debt service is about 11% of expenditures (#7), city pensions keep getting stingier (#8), and the city has a general fund balance that could cover over 30% of its yearly expenses (#10).

Another, more serious article by professors Craig Maher and Karl Nollenberger at the University of Wisconsin Oshkosh suggest some additional metrics you could use to evaluate a city’s financial health, like:

How much revenue is there per resident? A decline in per capita income over time could be a cause for concern.

Revenue per Wauwatosa resident increased from $1,435 per person to $1,596 per person between 2011 and 2021, but you have to adjust for inflation. Once you do that, revenue per person has actually declined by about 10% over the last decade. But honestly, it seems like 2011 was a strangely high year, and mostly the number has jumped around between $1,240 and $1,358 over the last ten years, and it doesn’t seem like this is worth getting very worried about.

How much money do they have for unexpected expenses? A city might have lots of money (fund balance) but sometimes the common council has earmarked it for a particular purpose or the federal government has placed constraints on how it can be used. What you really care about is how much is “unassigned” and available to spend in an emergency. Declining percentages of unassigned fund balances might signal a problem.

In 2011 about 86% of the city’s fund balance was unassigned and available for use in an emergency. This percentage declined sharply to a low of about 57% in 2013 but has since recovered to 85% in 2021.

The auditor specifically mentions this unassigned fund balance of $21.3 million as “very healthy.”

How well can the city meet ongoing service needs like hauling trash and delivering water? Measures of working capital (current assets minus current liabilities) are a good measure of this.

Unfortunately, there are no historical numbers, but current assets ($28.6m) minus current liabilities ($11.6m) leave $17m. I don’t know if this is good or bad but it’s not zero. Seems good?

How much long term debt does this city have as a percentage of its total assessed value?

This is actually something everyone pays attention to because state law limits this value to 5%. Since 2011 it increased from a level of 1.01% in 2011 to a high of 1.96% in 2016 but has since declined to 1.62% as of 2021.

There were a few questions that I was unable to answer very well, like:

How well funded are pensions?

I know that Wauwatosa does not have the same extremely generous pension benefits that have gotten other communities in trouble, that investments are handled by the Wisconsin Retirement System and that, unlike many state pension funds, WRS is 100% funded, relatively conservatively managed, and there are various ways in which municipalities are prevented from getting themselves into too much trouble. This article seems like a good summary. How this plays out in the 158 pages of audited financial statements isn’t entirely clear to me, and I’m just not sure how to evaluate it.

Is there an operating surplus or a deficit in the city’s general fund (the fund that your taxes go into and from which most transactions occur)?

I think this is on page 6 where it says in 2021 the city had $62.6 million in revenues and $51.2 million in expenses, leaving an excess of $11.4 million. But I’m not sure I’m looking at the right figures or that this tells the whole story.

But overall, as far as I can tell, everything they say seems true.

So congratulations, Wauwatosa. Looking good!

There's actually no data about the total number of employees in Wauwatosa but if you take 48,000 residents, subtract kids, senior citizens, and the unemployed, you get about 27,633 prime working age adults. If you add the 56,533 that commute into the city to work each day, you get a total of 84,166 employees, of which MRMC’s 17,000 comprise 20%. The next nine largest employers combined are only an additional 5,200 employees.

Although, technically, Wisconsin has no explicit law that actually allows municipalities to file for bankruptcy.

And about equal to the income of the average U.S. household since the average gets pulled up by extreme outliers.

Good to know! Thanks for the excellent information and analysis.